The Solitaire Mystery by Jostein Gaarder.

Phoenix 1997 (1990).

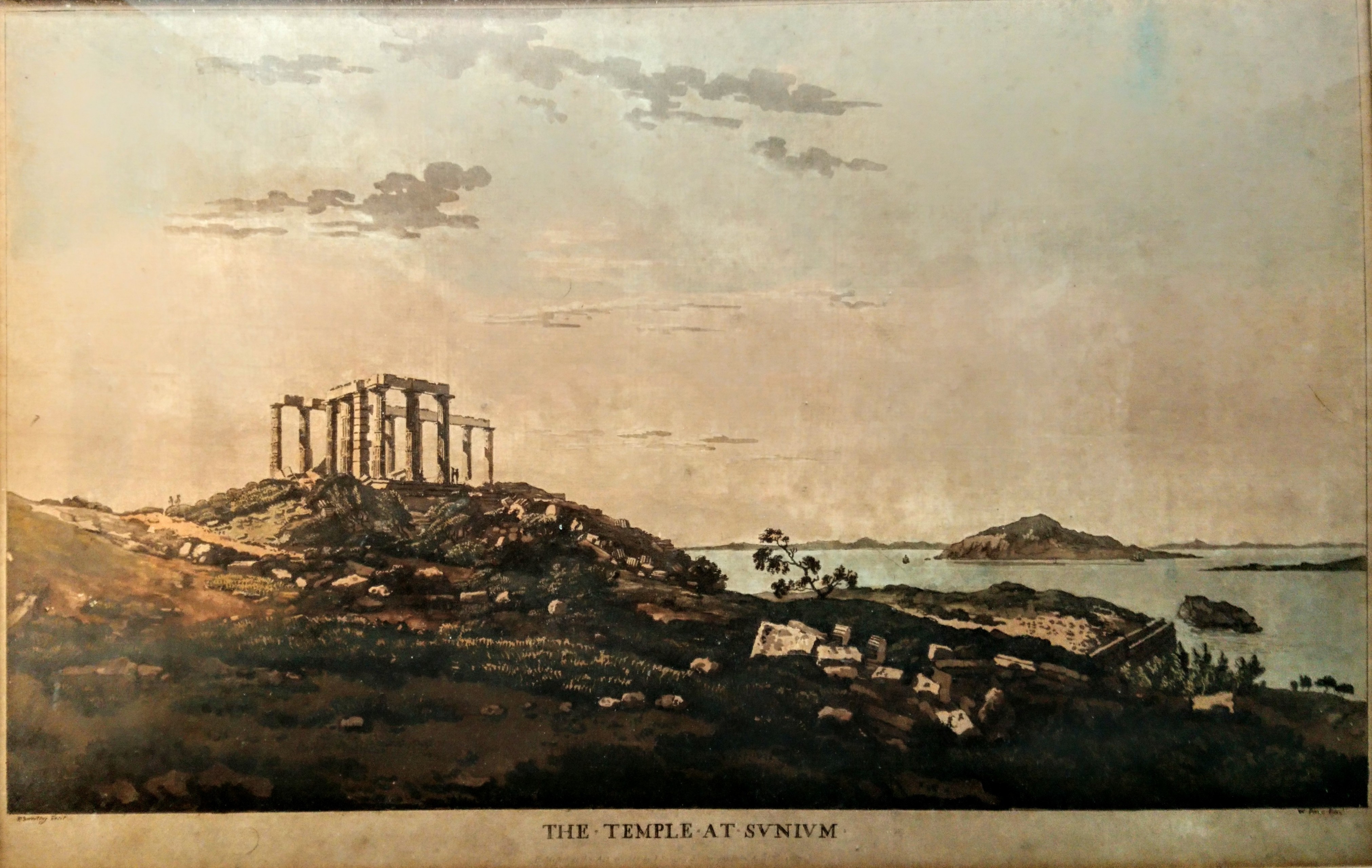

For nearly four decades I’ve had a hand-coloured aquatint by the Romantic artist Paul Sandby (after an original by William Pars). Dated 1780, it depicts ‘The Temple of Sunium’, the ruins of which edifice still lie at the last cape every sailor sees sailing south from Athens.

It’s not a very distinguished print (my copy is blemished by water marks) and I don’t know why I particularly liked it then, but I now treasure it for its classical associations: the site from which King Aegeus threw himself into the sea when he thought that his son Theseus had been killed by the Minotaur in the Cretan labyrinth, and a place of worship dedicated to Poseidon, Greek god of the ocean and of earthquakes.

I was reminded of this picture at a highpoint of The Solitaire Mystery, when Hans Thomas and his father hope to finally see his mother Anita, who left them back in Norway many years before in order ‘to find herself’. After a journey in an old Fiat from Norway via Germany, Switzerland, Italy, the Adriatic, Delphi and Athens, father and son learn that the mother can be found at a photo-shoot in the temple at Sounion. Why she has left them, why they have sought her after many years of waiting, and what then turns out to be the eventual outcome, all this forms the frame of the story, a metaphor for the philosophical quest that Hans Thomas and his father are simultaneously engaged in on their transcontinental trip.

Published a year before the best-selling Sophie’s World, this novel shares some of the same philosophical curiosity but somehow lacks the spark that makes it a great book, an omission that I find hard to put my finger on.

Gaarder’s narrative relies on the device of stories-within-stories, and concerns several lifetimes over some two centuries. Besides Hans Thomas and his ex-seaman father, the principal characters are Frode, who disappeared at sea in 1790, a baker called Hans who gets shipwrecked in 1842, Albert Klages who is an orphan from Dorf in Switzerland, and a German soldier called Ludwig who has an affair with a Norwegian woman before the end of the Second World War and is presumed dead on the Eastern Front. How these several lives interact, overlap and influence each other is a strand in the novel which is often confusing, I suspect deliberately so.

These links are compounded by The Solitaire Mystery being part of a genre in literature where there is a fantastic overlay to everyday life. In The Solitaire Mystery this largely concerns the recurrent theme of a pack of fifty-two playing cards with the addition of a Joker. There may be echoes of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland in Gaarder’s concept of cards existing as living individuals, and of Italo Calvino’s The Castle of Crossed Destinies in that the narrative seems to rely on a playing card sequence (Tarot cards in the case of Calvino’s novella) to determine the course of the action.

Gaarder, however, has used his cards to different effect: for example, they are introduced partly to demarcate the passing of days, months, seasons and years as a kind of universal calendar, with the Joker representing the extra day added in a leap year. The Great Year of fifty-two calendar years also has significance in the scheme of things, marking both an end and a beginning. I suspect the fact that the author was born in the fifty-second year of the twentieth century may have a bearing on his obsession with the numerology of playing cards.

As with many magic realism novels, the psychological aspects mingle freely with the fantastic, leaving lingering after-images long after the novel has been read. The recurrent motifs of sticky bun and fizzy drink may represent mere sustenance, or may have a religious significance; the special drink called Rainbow Fizz may refer to the father’s alcoholism or to one being so drunk with the sensation of living that one can become desensitised to the real wonders of life, the universe and everything.

The names that authors choose for places and people can take on a higher meaning (Hans Thomas notes that his missing mother’s name, Anita, is nearly a palindrome of the Greek word for Athens, where they are searching for her); or they may merely be coincidence (the Swiss village Dorf, which in German merely means ‘village’, is virtually a palindrome of Frode, ‘clever’ or ‘wise’ in Scandinavian languages); on the other hand, Gaarder may just choose names that appeal to him (a 20th-century philosopher and graphologist Ludwig Klages seems to have inspired the names of the German soldier Ludwig and his mentor Albert Klages). The more you dig, the more you uncover, which may be what Gaarder is trying to say about philosophy generally.

While this is an imaginative novel, bubbling over with mental pictures and ideas, I was not entirely convinced by the attempted meld of realism and fantasy; I would, however, be a little poorer for not having read it. An added bonus is the inclusion of Hilda Kramer’s illustrations for the chapter headings, both reminiscent of 19th-century engravings and notable for subtly including what look like fingerprint whorls for line shading.

I can’t speak for the accuracy of Sarah Jane Hails’ translation, but it certainly flowed naturally, capturing some of the phraseology and vocabulary that you might expect from the putative twelve-year-old narrator. If only all youngsters on the cusp of adolescence could have such insight; if only everyone had chances to ponder the inter-relatedness of things, as I did with an old aquatint and a sailor’s yarn.

Repost of a review first published here 29th August 2012

Well, I’m sold. It sounds an amazing read to me, Chris.

LikeLike

It’s not a great novel, but it’s certainly memorable, not one of those you pick up years later and think Have I already read this or not?

LikeLike

Well, I’m not a fan of Gaarder, I must admit. Sophie’s World left less than a lasting impression on me, and this one sadly doesn’t appeal. But you make it sound intriguing, Chris, which is more than I could say about Gaarder 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

I must admit I don’t remember much about Sophie’s World, Ola, and at the moment I’m not inclined to read it again. This earlier novel was a little more engaging — but then it’s an ideas novel more than anything, and I didn’t particularly engage with the characters, even though you’d think any road trip fiction would allow allow the reader to get more under the skin of the protagonists.

The only other book of his I’ve read, The Christmas Mystery, was way too cloying for my taste, and involved angels (which are nearly always an indicator of dubious worth unless handled with a degree of cynicism). I have a copy of his Maya to read, but I’ve not looked much beyond the blurb as yet.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lest old aquatints be forgot?

This is far out of the scope of my knowledge. Should it not remain so?

LikeLike

Should old aquatints be forgot and never brought to mind? For the sake of auld Jostein, let’s take a cup of kindness…

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve never read either of these but of the two I think this one would appeal to me most. (I think Sophie’s World is still being used by some teachers to draw students into the discussion of various philosophical elements.) Also, I love the idea of gathering together a few books/stories which feature playing/fortune-telling cards. It also seems highly suitable that you wander into your post via the print in the same way that it seems some of this story prioritizes wandering between stories too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love the idea of stories within stories or overlaying each other. Some storytellers use prompts such as cards to spin out their improvised narrative, don’t they, and of course images of any kind will do as a substitute. Glad you liked the intricate patterns I tried to draw out!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I read a few of Jostein Gaarder’s books years ago and remember really enjoying both this one and Sophie’s World, but I’m not sure whether I would like them now. My tastes have changed a bit since then, I think. Maybe I’ll try re-reading them one day, though I’m not in any hurry at the moment.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My thoughts too, Helen. Different stories and modes of narrating suit us at different times, I feel, according to maturity or mood. I think by the time I’ve read Maya I may have ‘done’ Gaarder as far as I’m concerned.

LikeLike