From The Meadows of Gold

by Al-Masʿūdī,

translated by Paul Lunde and Caroline Stone.

Penguin Great Journeys No 2,

Penguin Classics 2007 (947)

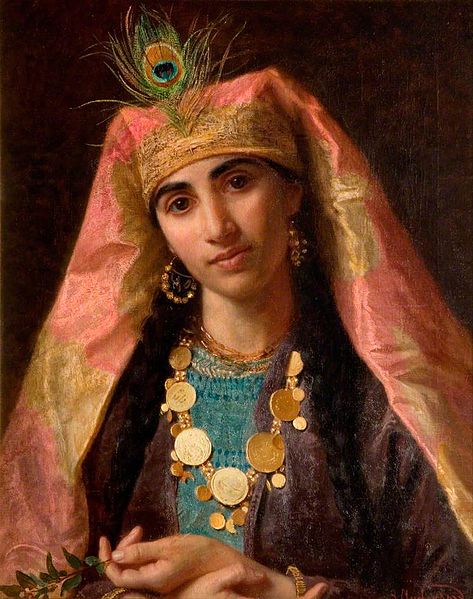

The author of this book compares himself to a man who, having found pearls of every kind and every shade scattered here and there, gathers them into a necklace and makes them a precious piece of jewellery…

’80. The author addresses his readers’

Born in Baghdad at the tail end of the ninth century CE, Masʿūdī or Al-Masʿūdī was intensely curious about the world around him, becoming an indefatigable traveller, researching and interviewing informants before authoring several original works.

Though only a couple of these books have survived the intervening millennium enough remains for Paul Lunde and Caroline Stone to have chosen and translated several chapters from a multi-volume work entitled The Meadows of Gold and Mines of Precious Gems, plus a few from The Book of Admonition and Revision. Taken as a whole their selection gives a good general impression of Al-Masʿūdī’s approach and the scope of his vision.

From this we can gather that he seems to have travelled extensively in the Middle East, perhaps in the role of a merchant trader, along the coast of the Indian subcontinent and very possibly through the East Indies, past Indochina and up to Guangzhou or Canton (here called Khānfū). What comes through are the very well-established trade and cultural connections right across the Old World, from Europe to Korea, connections which later writers such as Marco Polo and Sir John Mandeville were also to take full advantage of.

In this translation Al-Masʿūdī comes across as a chatty companion, begging our indulgence for any mistakes or negligence due to his failing memory and exhaustion after a lifetime’s voyages. He immediately lists the lands visited, the medieval equivalents of modern Azerbaijān, Syria, Pakistan, Zanzibar in East Africa, Vietnam, Sumatra and China. He mentions the western end of the Mediterranean, but though it’s clear he has never been there he is familiar with the history of Muslim rule in Andalusia.

There are short chapters on the Franks, Lombards, Slavs, Norsemen and Viking raiders; he recounts how the Khazars had relatively recently converted to Judaism, a detail that Arthur Koestler was later to use in his The Thirteenth Tribe to buttress the theory that Ashkenazi Jews are descended from the Khazar tribes; and he includes lengthy historical notes on other peoples (such as the Bulghārs and the Alans) in the Caucasus region. He doesn’t neglect religions such as Judaism, Christianity, Buddhism and Zoroastrianism either, to all of which he gives a fair hearing (as these his concluding remarks make clear): “May the reader rest assured that I have not here taken up the defence of any sect, nor have I given preference to this doctrine or other.”

The Meadows of Gold is full of anecdotes and asides, which gives some respite from a catalogue of polities, the names of rulers or mention of scholars which the author had met or whose work he respected, digressions which in fact leaven his narrative. We hear for instance of the vizier’s daughter Shirazad and her stories in Hazar Efsaneb (‘The Thousand Tales’, which we know better as Scheherazade’s The Thousand and One Nights); we’re also entertained with electric catfish and the rhinoceros, the banyan tree and backgammon, pearls and ambergris, cowrie shells and camphor. The further east we go hearing of lands which the author wouldn’t have visited — Tibet, say, or Qimār (Khmer in Cambodia) — the more the anecdotes proliferate. The edge of the known world for him was al-Sīla or Korea “and the islands belonging to it” where the air is healthy, the waters clear, the land fertile and nothing is in short supply — or so he will have been informed.

This short volume in the Penguin Great Journeys series is helpful in emphasising how cosmopolitan an outlook was held by enlightened scholars of the period, at a time when Barbarian Europe was emerging from the turmoil of its Migration Period. This translation usefully gives modern equivalents to places that might otherwise puzzle us, and a couple of maps are also included to aid orientation; and for western readers Al-Masʿūdī’s plentiful dates in the Muslim calendar are glossed with Common Era dates. This abridgement of The Meadows of Gold introduces us to a writer who could be both a devout Muslim and an enquiring humanist, and I for one feel all the better for being acquainted with him.

I find ‘travel’ writings from the past rather fascinating and this sounds like it is one as well; outsiders/foreigners or other people’s views of places one knows are interesting in themselves and time period adds to one’s interest.

LikeLiked by 1 person

There should be something to interest anyone familiar with any one of the regions discussed here. Al-Masʿūdī’s voice is a very distinctive one, even in translation, and it’s interesting to observe him switching from giving factual details to being chatty about something that’s intrigued him or a story he’s been told. And it’s quite a slim volume in this selection!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Will add this to my list.

LikeLiked by 1 person

😊

LikeLike

I’ll be sticking that on the longlist.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good to hear! Hope you enjoy it when you get to it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This sounds fascinating, Chris – thanks for sharing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I do love a bit of historical and geographical context!

LikeLiked by 1 person

He sounds a very interesting companion, Chris. I’d like to make his acquaintance. I hadn’t heard of him – how did you come across the book? Was it serendipity? I’d not heard of the Penguin Great Journeys series, either. I’ll have to check that out.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Serendipity for sure, found on some secondhand bookshelves a couple of years ago though I forget the occasion. The Great Journeys series titles listed on the back of this copy all appear to be equally slim volumes, culled from works by travellers ancient and modern, so worth seeking out if that appeals to you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

It definitely does appeal to me. I’ll keep an eye out in the Penguin sections of secondhand bookshops.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Great Journey series is still generally available, as here: https://www.worldofbooks.com/en-gb/books/series/penguin-great-journeys

LikeLiked by 1 person