Marco’s Pendulum

by Thom Madley

Usborne 2006

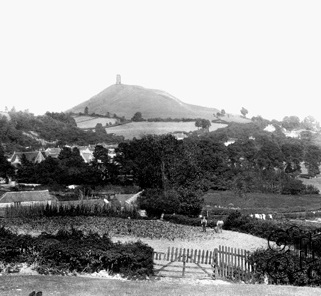

The cover blurb gives it away: Is the Holy Grail buried at Glastonbury, or something much darker? Well, of course, you know the answer to that, because this would otherwise be a rather tame young adult novel.

Townies Marco and Rosa find themselves separately set down in Somerset, both saddled with parents who don’t seem to understand them and set about both by bullies and by strange and very unsettling psychic experiences.

Pretty soon they find themselves thrown together and flung into a claustrophobic labyrinth under Glastonbury itself (reminiscent of the endings of both Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Alan Garner’s The Weirdstone of Brisingamen) in a narrative that is hard to put down and preferably not to be read at night. Well, not by adults anyway.