Too Loud a Solitude

by Bohumil Hrabal.

Příliš hlučná samota (1976)

translated by Michael Henry Heim.

Abacus, 1993 (1990).

‘I looked up and realized that Jesus and Lao-tze had disappeared up the whitewashed stairs like the turquoise and velvet-violet skirts of my Gypsy girls before them, and looked down and realized that my pitcher was empty, so I stumbled up the stairs on all threes, my head spinning from too loud a solitude . . .’ — Chapter Four.

In Prague, in what is now the Czech Republic, Haňťa repeatedly reminds us at the start of almost every chapter that for thirty-five years he’s been working alone in wastepaper, compacting it down in a hydraulic press. It’s hard work manually transferring waste dumped down a hole into his place of work to a compactor, binding the resulting bales with steel bands and moving them prior to being shipped out.

But Haňťa takes a certain pride in his work, consuming copious amounts of alcohol to energise himself before taking discarded books of philosophy and religion home to read, inwardly digest, and store precariously in his apartment.

New technology however is insidious, insinuating itself in communist Czechoslovakia as elsewhere in the 1970s; what will Haňťa do when his bullying boss has had enough of this drunken employee and decides to modernise, making Haňťa redundant? From the vantage point of an introvert like Haňťa can solitude ever be too loud?

A self-educated man who’s survived the country’s occupation by the Nazis and is now in a Soviet puppet state, Haňťa finds enlightenment in banned and redundant literature, in books on art and works by authors such as Schopenhauer and Kant, and absorbs ideas from Taoism, monotheism and existentialism. As a narrator Haňťa is both wonderful yet unreliable, making it often hard to tell what is true, what’s conjured up by intoxication and what’s pure imagination; yet in this novella’s seeming contradictions and dream-like episodes there are profound truths asking to be considered.

Much of the time Hrabal’s narrative feels like an attempt to reconcile opposites while simultaneously asserting that dichotomies are valid. Some examples: there are recurring references to the backwards and forward movement of the crusher working like smithy’s bellows, a machine over which Haňťa has control using red and green buttons; there’s also the photographer who claims he is snapping portraits of young gypsy women but whose camera may well be empty of rolls of film. Haňťa describes playing a trick on a furtive academic by pretending to be both the young worker and the older boss; meanwhile at work he has hallucinations, visions of a young Jesus as an optimistic spiral and an agèd Lao-Tse as a closed circle.

Like the author did in real life, Haňťa admires an uncle’s passions and ethics; after the uncle’s untimely demise Haňťa considers a quote from Immanuel Kant could be a fitting epitaph: “Two things fill my mind with new and increasing wonder—the starry firmament above me and the moral law within me.” The cosmos and individual morality, life and death, love and hate – like beauty and the grotesque can we see these pairs as complementary opposites, yin and yang as it were? Or is that the equivalent of trying to square the circle?

In Haňťa’s moving story we’re confronted with a meditation on the twin polarities of moving forward or going back, progressus ad futurum or regressus ad originem. As he contemplates being unlucky in love and friendships, at the loss of family and employment, Haňťa gives himself a stern talking-to:

“From now on, my boy, you’re on your own. You’re going to have to force yourself to go out and see people and enjoy yourself, playacting until you give up to the ghost, because from now on it’s just one melancholy circle after another and going forward means coming back, that’s right, ‘progressus ad originem’ equals ‘regressus ad futurum’ and your brain is nothing but a hydraulic press of compacted thought.” — Chapter Eight.

Hrabal packs a lot into a short narrative, a restless sense of movement, a head-spinning kaleidoscope of ideas, images that lodge in the mind – at least, they lodge in my mind – containing far too many concepts to touch on in a brief review like this. But even as we identify elements of magic realism we recognise the novella’s basis in reality: in a varied career Hrabal actually did a stint as a baler of wastepaper, though not for the three and a half decades Haňťa keeps repeating to us lest we forget.

And the story’s conclusion, couched as ambiguously as the rest of the novella, seems in fact to accord with Hrabal’s own attitudes to existence and non-existence.

It’s the kind of book I will reread and find another layer every single time. An astounding work.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Deeply affecting too, though I find it difficult to pinpoint exactly why in words. Would you recommend I seek out Closely Watched Trains next? (Incidentally, I just checked and now clearly see that I read your review – I’d like to think what you wrote will have influenced me to pick up my copy in a charity shop last year!)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow, this sounds intriguing.

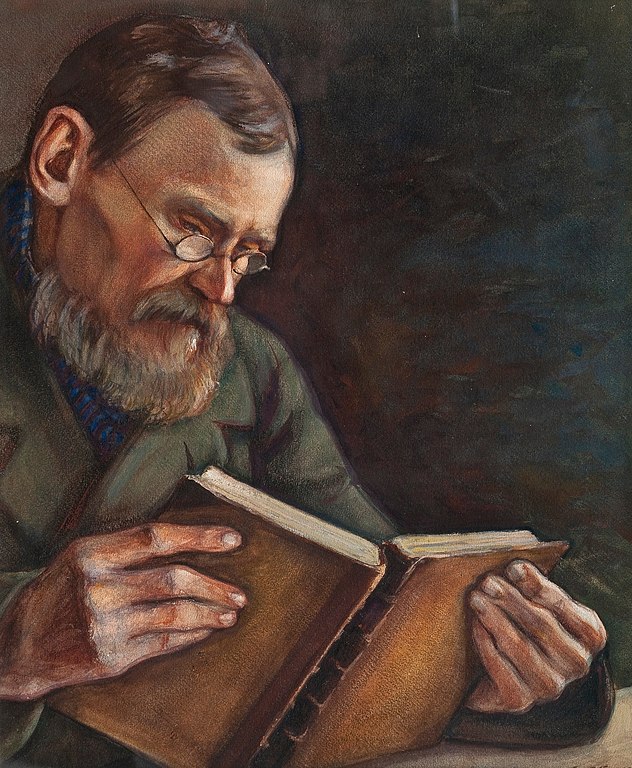

I love the painting you chose for this post 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is indeed intriguing, Lisa, the blurb a principal reason for me picking it up in the first place! As for the painting, I chose the image for a discussion on artworks showing readers and the man in this seemed an apt subject to hint at the protagonist.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I read this last year and some of it has really stayed with me. The imagery included is wonderful as you point out.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I must look out your review now, Cathy, if indeed you posted one. 🙂 It’s a haunting story as you say.

LikeLike

I did indeed Chris!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I see I not only ‘liked’ but also commented on your review, Cathy! Clearly the ghost of a memory of your review must’ve inclined me to pick up my copy last year and read it now. 😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree – I thought there was so much going on in this short book. It’s dark and I probably didn’t pick up all the references, but the hardest thing was seeing those lovely books destroyed…

LikeLiked by 1 person

The idea of books being pulped is always distressing, isn’t it, only mitigated here by the honour Haňťa shows them by where he places or displays them in his bales – such a contrast to the conveyor belt mentality of his planned replacements.

I suppose this is one of the principal themes Hrabal tries to bring out: if you’re going to destroy books at least do it with respect and retain a memory and understanding of what they teach, rather than the new-broom but philistine approach that new regimes tend to adopt.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hrabal is one of the Czech masters, I somehow always preferred Kundera. I don’t think I’ve read this one, I have to add it to the ever growing list 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not yet read Kundera, but I’ll get there eventually! I’m glad I read this one though, Piotrek, and I think you’d appreciate it too.

LikeLiked by 1 person