[Amabel] went straight to the Big Wardrobe and turned its glass handle. ‘I expect it’s only shelves and people’s best hats,’ she said. Of course it wasn’t hats. It was, most amazingly, a crystal cave, very oddly shaped like a railway station. It seemed to be lighted by stars…

E Nesbit, ‘The Aunt and Amabel’

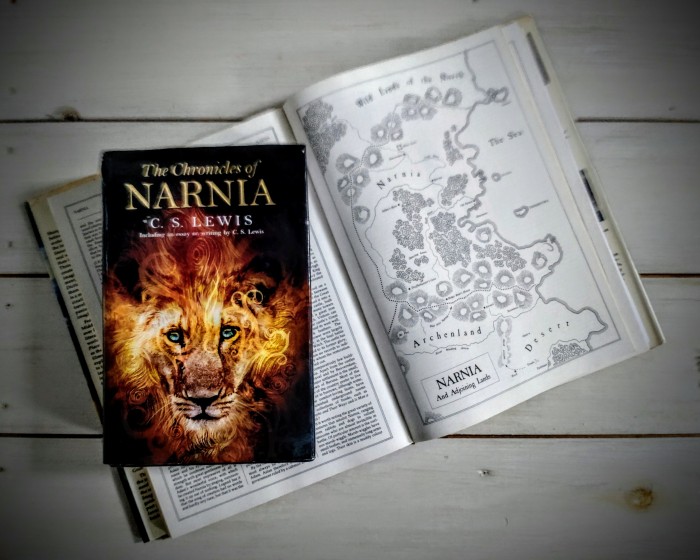

Having previously reviewed The Magician’s Nephew (1955) – but in advance of a scheduled review of E Nesbit’s The Story of the Amulet (1906) – I now want to discuss C S Lewis’s indebtedness, both generally and specifically, to his predecessor for not only details but also his general approach to the Chronicles of Narnia.

Not the least of his indebtedness is to Nesbit’s story ‘The Aunt and Amabel’ in The Magic World, in which a well-meaning little girl goes through a wardrobe to a place called Whereyouwantogoto and meets The People Who Understand – does this not sound a teensy bit familiar? I also want to enlarge a bit on aspects of the themes which Lewis introduces to The Magician’s Nephew that weren’t borrowed from Nesbit but yet which mattered enough for him to include in the novel. (When I say “a bit” it appears I mean “quite a lot”. Sorry about that.)

And here, as an aside, I shall just mention in passing other titles that play on aspects of Nesbit’s The Story of the Amulet, namely Diana Wynne Jones’s The Homeward Bounders (1981) which heads in a very different direction from that which Lewis took, and Edward Eager’s Half Magic (1954) which while very much sharing Nesbit’s sympathy for the child also involves some North American children discovering a mysterious talisman not unlike the amulet.

First, though, I’d like to consider the fact that both Lewis and Nesbit were known to their friends by different names. From the age of four Clive Staples Lewis preferred to be called Jack, apparently after a dog named Jacksie which, sadly, was then run over in traffic. Meanwhile, Edith Nesbit was known to her family as Daisy – in a poem about the flower she describes them as “Pretty and proud in their proper places, | Millions of white-frilled daisy faces,” and in one of her Bastable books (The Wouldbegoods, from 1900) there’s even a rather insipid character called Daisy.

(Another author more or less contemporary with Lewis, Muriel Jaeger, was dubbed ‘James’ or ‘Jim’ at university by fellow students (such as her friend Dorothy L Sayers) in their Mutual Admiration Society, and it’s remarkable that her debut novel, the dystopian The Question Mark (1926), overlaps with certain themes in The Story of the Amulet, involving as it does time-travel to the future, dreaming, and theosophy.)

At the very start of The Magician’s Nephew Lewis sets the scene around the year 1900 by telling us that the action happens when Sherlock Holmes was doing his detecting and Nesbit’s Bastable children were rattling around Lewisham in London. Here he slightly misdirects us, for his novel – and indeed much of the Narniad – pays homage not to the Bastable stories but to Nesbit’s Psammead trilogy, and in particular to The Story of the Amulet. The Psammead stories (Five Children and It, The Phoenix and the Carpet and the amulet story) mostly feature four active children from 1905 called Cyril, Anthea, Robert and Jane, with whom we may usefully compare the Narniad’s Peter, Susan, Edmund and Lucy. But the Nephew and Amulet stories have several specific aspects in common.

- Nesbit’s children have absent parents, a father in Manchuria and a mother who’s gone abroad for her health; Lewis focuses mainly on Digory Kirke’s mother, who is very poorly and likely to die (as Lewis’s own mother did when he was around the same age as Digory), but there is also joy when the boy’s father returns from India.

- Nesbit has a learned gentleman with whom the children come in contact, an expert in Mesopotamian antiquities and history; Lewis has Digory’s uncle who happens to dabble with magic, though he is less likeable than Nesbit’s scholar.

- Nesbit’s gentleman has a lodging upstairs from where the children are staying; Lewis’s magician is met when Digory and his friend Polly explore the attics of the house he is staying in. One could be said to live in a virtual ivory tower while the other conforms to the archetypal wizard figure in their study or laboratory.

- Nesbit’s Anthea is the most sensible and proactive of the four youngsters, possibly a reflection of what the author imagined herself to be; Lewis’s Polly often also takes a leading role in her partnership with Digory, such as when fruitlessly advising him not to ring the bell in Charn that then wakens the Queen of that city.

- Nesbit has the Queen of Babylon visiting London, travelling in a horse-drawn cab and inadvertently causing mayhem; Lewis has Jadis, the Queen of Charn, magically drawn to London at that same period, also travelling by cab and also causing mayhem.

- Finally, Nesbit’s Egyptian amulet is the magical talisman that allows travel between 1900 and past and future eras; Lewis instead has magical rings that take the children and others, via the Wood Between the Worlds, to other lands like Charn and Narnia.

So, is Lewis’s novel simply a copy of Nesbit’s? No, not really: there are differences, principally in tone and motive. Here is Nesbit writing about the class of adults to which she believes she belongs, in which they

just mingle with the other people, looking as grown-up as any one — but in their hearts they are only pretending to be grown-up: it is like acting in a charade. […] And deep in their hearts is the faith and the hope that in the life to come it may not be necessary to pretend to be grown-up.

Eleanor Fitzsimons, ‘The Life and Loves of E. Nesbit‘

She needed to pretend to be grown-up in this life but under the surface she retained child-like wonder, values, emotions: and it was these qualities which made her writing so unpretentious and accessible to her intended readers – she was one of them and saw things from their point of view. Lewis on the other hand could not help but be avuncular, talking down to his readers, mansplaining to all and sundry any moral he intended his narrative to convey. To be fair, though, he did aim to capture much of the wonder and enchantment which Nesbit, his model, demonstrated in her children’s fiction, and in this respect he was largely successful. As he wrote,

“Beware the unenchanted man.

Talking About Bicycles, from ‘Present Concerns’

To the child, from the beginning, life is the unfolding of one vast mystery; to him our stalest commonplaces are great news, our dullest facts prismatic wonders.”

He talked about four ages or stages of wonder that adults can go through, namely Unenchantment, Enchantment, Disenchantment, and Re-enchantment; and it’s clear he understood those stages having been through them himself. But these aren’t the same as when Nesbit sensed being forced to pretend to be grown-up when she still felt child-like: Lewis felt his enchantment had matured but Nesbit knew she retained her child essence.

I think the difference comes with Lewis seeing himself as the perennial teacher; and this made him aware that he had to show himself as being both an authority and in authority. And his religious stance meant there was an added sense of morality to be got across, more or less explicitly. Contrast this with Nesbit writing at the end of “The Mixed Mine” (in her short story collection The Magic World): “There is no moral to this story, except… But no – there is no moral.” She allowed her readers to draw what they wanted, or maybe needed, from her fiction for themselves; conversely Lewis had need to add or at least imply a lesson from his narratives.

So what specifically is there – other than a moral stance – in The Magician’s Nephew that makes Lewis’s narrative distinctive from Nesbit’s? I think much of it stems from Lewis’s identification of his childhood self with Digory Kirke’s position: both had a mother who was very poorly indeed. Crucially both Nesbit’s and Lewis’s books hinge on a chapter about the heart’s desire; but while Lewis was powerless to stop his own mother dying from cancer when he was nine years old, Digory was faced with a mighty moral dilemma: should he be tempted by the words of Jadis and steal a life-giving apple to save his mother’s life, or not?

With this apple we note that many choose to associate this and other aspects of this novel with Lewis’s Christianity. Thus the apple orchard bounded by a wall is referencing the Garden of Eden and the Temptation there, as recounted in Genesis; Genesis is also responsible for the description of Narniad’s Creation; and so on. But when creating his septad Lewis was nothing if not magpie-like: he borrowed themes and motifs from many cultures, traditions and legends, all of which got stirred into his cauldron of story along with hints of the Old and New Testament. Here are some examples:

- The apple tree within the walled orchard ‘on a green hill far, far away’ not only references the Garden of Eden but also the Garden of the Hesperides, guarded by a dragon far to the West, in which grew golden apples that conferred immortality. Norse myth also tells of the goddess Iðunn who has golden apples she feeds to the gods to keep them from growing old; Loki attempts to lure her away from her task, with potentially dire effects.

- When Polly and Digory are sent to the Wood Between the Worlds by the magic ring they discover that immersion in different pools takes them on to different worlds or universes. Is this a reference to baptism? Very likely, though of course Christianity is not the only religion to use ritual washing as symbolic of achieving a different state of being.

- The bell in the deserted city of Charn that fatally summons Jadis to life or wakefulness is a common folk motif, of course. A good example is the motif of the sleeper or sleepers whose awakening will effect change in a social order: King Arthur for instance can be awakened by a horn or bell being sounded to save the country from disaster, but he mustn’t be roused without good reason, such as when a stranger intrudes by chance into the cave where he sleeps.

- Aslan sings Narnia into being, which is quite unlike the account in Genesis (though St John’s gospel has the World being created by Logos, the Word). The most famous classical singer was of course Orpheus: as Shakespeare wrote, “Orpheus with his lute made trees, | And the mountain tops that freeze | Bow themselves when he did sing. | To his music plants and flowers | Ever sprung; as sun and showers | There had made a lasting spring.” And many cultures and fantasies link singing with creation – I am particularly reminded of Ursula Le Guin’s Earthsea books with their poetic refrain:

“Only in silence the word,

—’The Creation of Éa’

Only in dark the light,

Only in dying life:

Bright the hawk’s flight

On the empty sky.”

Oddly, Lewis chose to depict the beginnings of Narnia in this, the penultimate title of the Narniad, only to bring it to a close in the next, The Last Battle (1956). This, incidentally, being the final book in the series, is the last one which we’ll be considering in this Narniathon, in a post scheduled for the last Friday of this month; coincidentally the 24th June is the Christian feast of John the Baptist, commemorating the birth of the saint as well as the medieval equivalent of midsummer.

Eleanor Fitzsimons. 2019. The Life and Loves of E. Nesbit. Duckworth.

C S Lewis. 1955. The Magician’s Nephew. Fontana Lions, 1980.

E Nesbit. 1912. The Magic World. Macmillan Publishers, 1980.

Some great phrases here. I like “an authority and in authority,” reflecting on the role of the Mediaeval doctor as someone who is an auctoritas. This link https://blogs.bl.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/2012/05/royal-workshop-a-call-for-your-feedback.html has an image Lewis would recognise (if not this actual one, then similar).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Nick. I can’t claim any credit for the “an authority, in authority” distinction, which was drummed into me during teacher training. The pedagogical image is indeed one that must have been familiar in one form or another to Lewis!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think I shall be re-reading some Nesbit, (after Susan Cooper).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lovely! Are you still planning to run a monthly readalong from August of The Dark is Rising series, Annabel? I’d be up for that, as I’ve still the last two titles to read but would be happy to begin at the beginning again!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes I’m still going to read the Coopers.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I shall definitely join you.

LikeLiked by 2 people

One thing leads to another in a Narnian chain of imaginative being.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“A chain of imaginative being” is a great description, redolent of medieval cosmological thinking.

LikeLike

How fascinating, to see how indebted Lewis clearly was to E Nesbit! I suspect from what you say that, when I finally find time to re-read some Nesbit, I will find her general tone rather more congenial than Lewis’s!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re not wrong there, JJ! I think Nesbit not only understood kids (as Lewis did to an extent) she was able to talk to them, as opposed to Lewis who was rather inclined to talk at them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I guess ‘Once an Oxford don, always an Oxford don!’ 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

A tendency, as an ex-teacher, I have to curb in myself… 😬

LikeLiked by 1 person

LOL (as the young people say! Or perhaps they don’t anymore …)!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lmao is an alternative, while I think the term, for approval, is currently sick…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Really fascinating post, Chris, especially for someone like me who’s never revisited Nesbit. Lewis certainly wove an incredible amount into his stories!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Cheers, Karen. It’s been quite enlightening for me doing a slow second reading and reassessing the text I’d previously rushed through with some irritation because of perceived preachiness.

I had sensed Nesbit’s presence before though, and it was nice to then revisit the Amulet story to confirm my hunches.

LikeLiked by 2 people

More than Narnia, the reference to Edward Eager’s Half Magic is what caught my eye. I loved Half Magic, and unfortunately, I discovered it only recently; I wish I’d known about it as a kid. But what a brilliant book — it uses the “show, not tell” trick too so very well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Me too, I only read the Eager recently and thought it beautifully refreshing, and while clearly owing debts to Nesbit (that ‘show, don’t tell’ approach) very much its own self.

LikeLike

The reference to the Bastables stood out when reading The Magician’s Nephew but I hadn’t realised how much of an influence Nesbit was on Lewis, so thanks for pointing out all those similarities. And indeed all the other sources of inspiration that are too often put down to biblical/Christian allegory.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m glad this post was as informative as I hoped it might be, Mallika, I did really like researching it to confirm many of my hunches. And, though far be it for me to deny the undoubted Christian influences, I’m convinced that Lewis’s wide interests and reading provided as much, if not more, of the themes and motifs that permeate all the Narnia books.

LikeLike

I continue to learn a great deal from your thoughts on the Narnian Chronicles, Chris. Thank you. Now I need to read the Nesbit books that I missed out on.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s a pleasure, Anne, always good to know my thoughts aren’t just disappearing into a void! You remind me that, though I’ve watched the Lionel Jeffries film more than once – and still get choked up by Bobby’s “Daddy, my daddy!” – I still haven’t read my copy of The Railway Children.

LikeLiked by 1 person