“Never judge a book by its cover, except if it’s a Jeffrey Archer”

— Traditional saying

If, when looking for a good read, we have already been attracted by a title or author or blurb, then that first opening sentence is crucial — especially in an age of channel-hopping, soundbites and eight-second attention spans. Have you switched off yet?

As with all specialist literature, Arthurian prose literature should predispose the sympathetic reader to read on, not move on. Here, for that reader, is the beginning of the classic example of that literature, from the fifteenth century:

Hit befel in the dayes of Uther Pendragon, when he was kynge of all Englond and so regned, that there was a myghty duke in Cornewaill that helde warre ageynst hym long tyme, and the duke was called the duke of Tyntagil

(Thomas Malory, in Vinaver 1954).

How did that grab you? Are you on the edge of your seat? Or are you yawning already? And do 20th century re-tellings of Malory follow that pattern?

In the old days, as it is told, there was a king in Britain named Uther Pendragon (Picard 1955).

This is clearly a literary descendant of Malory, but some concession has been made for a juvenile readership in that it is shorter and punchier without losing its poetic, almost biblical cadences.

Here is another opening:

After wicked King Vortigern had first invited the Saxons to settle in Britain and help him to fight the Picts and Scots, the land was never long at peace (Green 1953).

A lot of information is offered, and assumptions made about prior historical knowledge. For this version, the author’s principle is that “the great legends, like the best of the fairy tales, must be retold from age to age: there is always something new to be found in them, and each retelling brings them freshly and more vividly before a new generation” (Green 1953, 13). There are some value judgements here, aren’t there? Malory is not vivid enough for us moderns; and Retellings are always fresh. In some instances there may be an element of truth in these assumptions. Here now is the beginning of T H White’s re-casting of Malory:

On Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays it was Court Hand and Summulae Logicales, while the rest of the week it was the Organon, Repetition and Astrology (White 1958).

There is nothing here initially to suggest an Arthurian setting, but the combination of whimsy and exactitude may be sufficiently intriguing to draw a non-Arthurian further into the book. This is certainly both a vivid and a fresher approach to the Matter. How have other Arthurian authors approached their craft?

This brief review of beginnings in Arthurian fiction will be limited in the main to novels from the last four decades of the 20th century but set in the Arthurian period — however that is perceived — pulled randomly off my shelves. There is no attempt at all at completeness; fiction using themes from the Matter but set in the present day will be excluded, though only for the sake of manageability.

Persia Woolley has noted that “during the last half of this century the authors of novels based on the stories of King Arthur have more or less divided into three categories: those who cast the stories as fantasy, those who see them as ‘women’s romance’, and those who give them a realistic treatment” (Woolley 1991, 11). These categories have provided a rough framework for discussion.

In addition I have sometimes borne in mind an observation on the openings of many works of fantasy, namely that “the reader is poised on the very brink of an abyss right at the beginning” (LeFanu 1996, 26), as a criterion to assess the effectiveness of their initial sentences.

Historical realism

Woolley herself claims that her own Guinevere novels belong in the realistic category. In the second volume of her trilogy she notes that “the historical novelist always faces the problem of anachronism and must make the choice between contemporary readability and historical accuracy. In my case I’ve opted for readability, or occasionally for tradition” (Woolley 1991, 13):

I, Guinevere, wife of King Arthur and High Queen of Britain, dashed around the corner of the chicken coop, arms flying, war-whoop filling my throat (Woolley 1990).

There’s certainly readability here, and an arresting image, but anachronisms later abound despite evidence of wide research on Dark Age Britain. Henry Treece tried to avoid anachronism by eschewing all later traditions: “all I know is that Malory and Tennyson were wrong!” he wrote in a preface to The Great Captains. This novel begins with an epistle in late classical style:

Letter from Cynon, in Britain, to Gerennius, in Gaul: 477 AD. Honoured Kinsman and Friend, This, in an extremity of grief and danger, my last to be written to you: for tomorrow we leave this broken house, such of my family as are still living (Treece 1956).

His later Arthurian novel, incorporating the primitive aspects of the Hamlet story, uses the same epistolary device:

To the Duke and Honourable Pastoral of Puteoli, Golden Mouth, Lord Manuel Chrysostom in the Hand of God and at the Foot of Mary: from the humblest of his servants, Gilliberht of Fiesole, monk in the House at Arles, in the year of Our Lord 526 (Treece 1966).

The exaggerated tones of these stock formulae decidedly root Treece’s fictions in a known world of late antiquity. The content of the epistles make it clear that that we are in a crumbling post-imperial period, and that for the writers this is certainly the “brink of an abyss”. However, for the modern reader the literary circumlocutions, though authentic in style, slightly detract from the sense of urgency.

Rosemary Sutcliff also echoes the fin de siècle atmosphere in Sword at Sunset, but chooses to start near the end, almost with a whimper, with Arthur in the Isle of Apples:

Now that the moon is near to full, the branch of an apple tree casts its night-time shadow in through the high window across the wall beside my bed (Sutcliff 1963).

No stilted memoirs these; instead, we have long brooding, regretful reminiscences about a long life achieving … what?

Gillian Bradshaw also opts to open Kingdom of Summer with a sense of place (Somerset again):

Dumnonia is the most civilized kingdom in Britain, but in the northeast, in January, it looks no tamer than the wilds of Caledonia (Bradshaw 1981).

Again, a sense of tragedy overhangs all, a hand-to-mouth existence, with death, like winter, omnipresent. And although preceded by Hawk of May you just know that any optimism will be dissipated by In Winter’s Shadow, the last of her trilogy.

Even in Helen Hollick’s first volume in her Pendragon’s Banner trilogy, the transitory nature of Arthur’s life and apparent achievement is implicit in that little phrase, the worm in the bud, “for this short while”:

He was ten and five years of age and, for the first time in his life, experiencing the exhilaration of the open sea and, for this short while, the novelty of leisure (Hollick 1994).

The doom-laden atmosphere re-appears in the first of Fay Sampson’s sequence Daughter of Tintagel:

It was the worst thing we ever did when we forgot Morgan, that night above all nights. (Sampson 1989)

Most of these historically-based novels (even Woolley’s, with its example of lèse-majesté) play heavily on a sense of foreboding or continuing misfortune right from the word go. It is part of a long tradition, all the way from Gildas, in which the plucky underdog despite a good fight inevitably loses out to insurmountable odds. It is all deeply depressing, but then that’s tragedy for you!

Romance

Despite Persia Woolley’s claims, her Queen of the Summer Stars lies, I suspect, closer to what she calls ‘women’s romance’ than historical fiction — there are too many pre-echoes of Malory for anyone to believe that hers is a serious reconstruction of sub-Roman Britain.

So what exactly is modern Arthurian romance? I would guess that it is a novel where the outward world of physical action is closely reflected by internal worlds of emotion, and where the final mood is one of optimism. Sharan Newman’s Guinevere might be so described, and begins thus:

There was a sound in the night (Newman 1981).

The sound is related to voices that she hears and, in time, to a unicorn which tries to save her from harm. Despite the fantasy elements this is a novel where human love and religion are manifestations of a world of emotion, providing an interesting twist to the familiar tale, and where there is an upbeat ending of sorts.

Fantasy

We turned our horses and rode into that terrible dark wood – the Lady Morgan le Fay, myself her fifteen-year-old niece, and the four silent serving-men that followed us (Chapman 1975).

With these words the late Vera Chapman begins her fantasy trilogy The Three Damosels. What is fantasy? As Sarah LeFanu has pointed out, “nobody has come up with a hard and fast definition of fantasy”, though she does list some of its concerns: the unexplained, the unexplainable; magic and mystery, and sometimes the supernatural; very often a secret is at its heart (LeFanu 1996, 3f). The opening of The Green Knight quoted above hints at these concerns, and in due course delivers.

Merlin’s Ring on the other hand is set not in one epoch but in many, and in many Never-Never Lands:

Five days out from Streymoy, in the Faroes, having been borne far into unknown seas by a violent westerly, the little fishing boat came to a new land and a fair day (Munn 1974).

The action is far different from the superficially similar opening of Hollick’s novel. Gwalchmai is the protagonist, but not the Gwalchmai we might expect, nor even the Sir Gawain of Gwalchmai’s later incarnation. Here we are mostly far away from Camelot, Joyous Gard and the rest, though Arthur’s tomb is visited, close by St Michael’s Mount in Cornwall, to return Excalibur.

In Monaco’s Parsival, the story starts innocently enough:

The field was like a lawn (Monaco 1977)

but the action soon outstrips this idyllic scene. Gone are the dreamlike images of knightly quests, here instead are churlish doings in a nightmare landscape. Wolfram’s version of the story is the basis for this exploration of grail themes and the meaning of life.

In an even darker mode is The King’s Evil:

The guards came down from the city at dusk (Middleton 1995).

This is the mainspring for a portrait of Mordred from his own point of view, a horrific dissection of the psyche of a figure part Judas, part Jesus; very nearly a victim in a massacre of the innocents, Mordred is certainly at the brink of the abyss from the start and, indeed, all the way through.

Happily ever after…

After this peremptory glance at some of the fanfare motifs of Arthurian fiction, can any conclusions be drawn?

It is clear that packaging sets the tone that the publisher wishes the consumer to perceive from their product, but most potential readers wish to believe they make their own minds up. In a world where often our leisure is as busy as work itself, and we fear that too much time spent on one thing means we are missing out on something better elsewhere, instant judgements on our purchases are mandatory. We need to recognise the quality we are searching for in a split second.

Like the opening credit sequence of a film an immediate connection has to be made. How this is done in fantasy fiction is varied: “One writer packs information into the opening sentences, another imbues them with atmosphere; … one shows intellectual conflict, another gives us intensity of emotion …”

But there is more than mere technique that is required. “In all of them, I think, there is a sense of words chosen so carefully that the resulting mix of images, ideas and rhythms in the very language suggest that if you read on you will enter a world that is well worth exploring … That is what gives those worlds their reality. Their writers believe in them.” (LeFanu 1996, 28).

If this is true of the modern fantasy genre, it is equally true of all fiction, and it should apply to Arthurian fiction. And the beginning should draw you in as surely as Once upon a time ever did.

References

- Gillian Bradshaw (1981). Kingdom of Summer [Signet 1982, New York]

- Vera Chapman (1976). The Three Damosels [Magnum edition 1978, London]

- Roger Lancelyn Green (1953). King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table [Penguin, Harmondsworth]

- Helen Hollick (1994). The Kingmaking [Heinemann, London]

- Sarah LeFanu (1996). Writing Fantasy Fiction [A & C Black, London]

- Haydn Middleton (1995). The King’s Evil [Little, Brown and Co, London]

- Richard Monaco (1977). Parsival or A Knight’s Tale [Futura Publications 1979, London]

- H Warner Munn (1974). Merlin’s Ring [Ballantine Books, New York]

- Sharan Newman (1981). Guinevere [Futura Publications 1984, London]

- Barbara Leonie Picard (1955). Stories of King Arthur and his Knights [Oxford University Press, London]

- Fay Sampson (1989). Wise Woman’s Telling [Headline Book Publishing, London]

- Rosemary Sutcliff (1963). Sword at Sunset [Penguin Books 1965, Harmondsworth]

- Henry Treece (1956). The Great Captains [Savoy Books 1980, Manchester]

- Henry Treece (1966). The Green Man [Sphere Books 1968, London]

- Eugène Vinaver ed (1954). The Works of Sir Thomas Malory [Oxford University Press, London]

- T H White (1958). The Once and Future King [Fontana Books 1962]

- Persia Woolley (1990). Guinevere, Queen of the Summer Stars [GraftonBooks 1991, London]

An article first published in Pendragon, the Journal of the Pendragon Society, Vol XXVIII No 2 (winter 1999-2000)

Good heavens! You really are on top form at the moment, Chris! What a selection – and what an eye for detail! This must have taken ages…

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Nick, it really did take ages back in 1999, but then editing an Arthurian quarterly journal in any spare time allowed by teaching and family was a labour of love anyway! Luckily I’d got this saved digitally so all I had to do was dust it off and bingo, another literature related post is available for a new audience. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

And a fascinating post it is too!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Cheers, Sandra, I think with writing this I finally got Arthurian fiction out of my system: I’d dutifully read many lacklustre books, fiction and non-fiction, in my editorial capacity, and had got to the point where I was seeing many the same themes and tropes being rehashed. This was my attempt to garner what literary merit I could from some of the books I had at the time on my shelves.

LikeLiked by 1 person

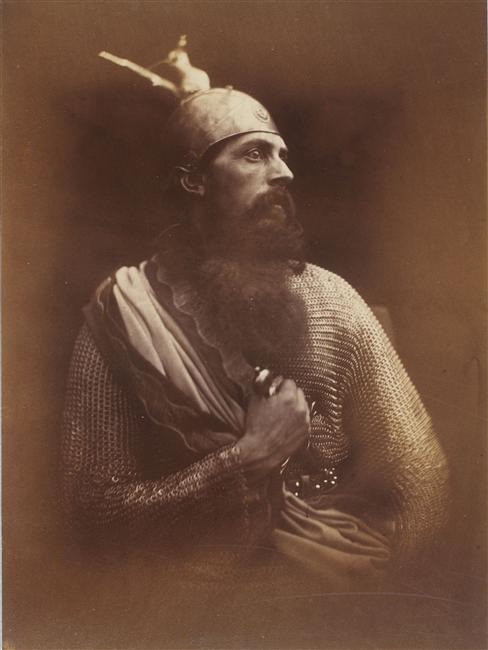

Good Lord, that picture at the top had my girlish heart beating like billy-o! I had such a crush on Oliver Tobias back in the day, and sadly had forgotten all about him in the interim. Now I’m twelve again… 😀

LikeLiked by 2 people

Ah, me too! 😆

LikeLiked by 2 people

I hoped that photo might draw in some bloggers, Sandra! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hah, I’ve no girlish heart, sadly, but I understand his heart-throb appeal!

I had various degrees of separation in connection with this TV series: living in Bristol at the time I was aware of the filming going on in this part of the West Country; and though the series played hard and fast with historical accuracy (which I was very much into at the time) I met Bob Baker, one of the writers, who went on to collaborate on the Wallace and Gromit films, for which the drummer in the folk rock band I was in did many of the props. Bristol was definitely a lively place, creatively speaking, in the 1970s!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Really interesting post (and I was never that attracted to Oliver Tobias, I’m afraid). But I get you about the opening lines – if a book doesn’t draw you in straight away it can be a battle from the start. I probably haven’t read much modern Arthurian writing – I was introduced to the subject by Mary Stewart in my teens, if I recall correctly, though I did read and love Malory and a number of others in my 20s (Chretien de Troyes too but I can’t be sure of the others). I prefer a bit of classical writing if I can manage it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, like you, Karen, I’m more interested in those medieval tales, and we’re lucky so many of them have been translated from French, German, Italian and other languages. I really should revisit those as I’ve still got copies on my shelves (which is more than can be said for most of the novels I reference here!).

I remember reading a curious retelling of Malory by Steinbeck, which was published posthumously—it transformed from a version in Modern English to a more imaginative and individual take which, sadly, he never lived to revise and complete. He worked on it while staying in Somerset, not too far (as it happens) from a Roman villa which I was involved with excavating outside the village of Bratton Seymour in the early 70s.

LikeLiked by 1 person

How interesting and such fab pictures! Sadly, we didn’t really watch ITV in our household, so I never saw this Oliver Tobias series which I would have loved, natch. I have read some of the books you mention which bring back memories: The H Warner Munn and Richard Monaco – read the sequels to each too; Treece, Lancelyn-Green and TH White too. I can’t remember if I ever read the Sutcliff, but I own a copy. Like Kaggsy, I devoured the Mary Stewart books, and also Marion Zimmer Bradley’s The Mists of Avalon.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I only watched a few of the episodes in the two series which aired, so can’t say I was a massive fan; one episode I vaguely recollect had a Bristol folk musician, Fred Wedlock, hamming it up as a medieval minstrel so embarrassingly that I think I stopped watching any more! There was a Welsh musician, Meic Stevens, who also featured as a minstrel with a more authentic approach but I don’t remember seeing him: https://arthur-of-the-britons.dreamwidth.org/22077.html

My personal preference is more for recontextualising Arthurian themes and motifs, especially in a modern context rather than a period retelling as historical fiction; so children’s authors like William Mayne or Penelope Lively, and adult novels by C S Lewis and Charles Williams who used contemporary settings to reintroduce Arthurian characters and tropes were more to my taste. I never read Zimmer Bradley but enjoyed The Crystal Cave and Andre Norton’s SF-tinged Merlin’s Mirror.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Vinaver’s edition, I actually enjoy. Admittedly, I think my only version of Malory on hand is the Oxford UP “Complete Works”, in Malory’s anachronistic attempt at early Middle English. Oddly, it’s a good intro to ME, since it’s pretty straightforward, even moreso than Chaucer.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What Malory did in his trawl through earlier Arthuriana in French and English is attempt to provide a composite of all that had gone before, whether or not they were consistent with each other or not. I remember a few years ago making a fairly desultory comparison between the Vivaver edition and a handful of text he’d likely consulted, and it’s interesting to see how faithful or not he was to his originals. Sadly, I can’t remember much of the conclusions, if any, I came to, other than it may’ve been possible to trace which sources he used from his inconsistent spellings of names.

I think what Steinbeck attempted was the next stage, a distillation of Malory much as Malory distilled his own sources. I agree, though, that Malory’s 15th-century language is a lot more accessible to us moderns than Chaucer’s from the early 14th century.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Most impressive. The Rosemary Sutcliffe is the one that would draw me in with its atmosphere and sense of place.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I hardly dare come back to the Sutcliff novel after a gap of half a lifetime: I know that there was a power there that my younger self recognised as being a bit like Mary Renault’s ability to transport you back to what felt like something authentic, something melding barbarity, sensitivity, tragedy, passion and inevitability. That opening has it with the shadows and the apple tree reminding us this is Avalon, the place of apple orchards

LikeLiked by 1 person

Beautiful

LikeLiked by 1 person

Totally awesome article! It’s so interesting that the choice of words in the first sentence of a story can be, and feel, so vastly different!

Reading your posts often feels like a “behind the scenes” glimpse of the literature involved.

PS: I hope Emily is continuing to recover and that you are both doing OK.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m chuffed over your ‘behind the scenes’ comment, Jo, as it’s often what I aim to offer. Those opening words tell me a lot about the care the author is taking to draw me in in terms of atmosphere, setting, point of view, and so on.

Emily is improving steadily, thanks, off painkillers and often not needing crutches except for confidence when outside. We got our first dose of Pfizer vaccine and I hope that, if you count as in a vulnerable group, you’ll be soon in line if not already vaccinated.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m glad she’s doing well. I was vaccinated this week – I had the Pfizer one too. I hadn’t realized how scared I’ve been of this illness until some of that fear lifted after the vaccine.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m so pleased that you’ve had it, that must be a huge weight off your mind. Roll on the follow-up jab! Are you still expected in school now?

LikeLiked by 1 person

No, I handed in my resignation. My health is still going down hill and I’ll need carer help a couple of times a week when my son returns to Uni. The doctors are thinking it might be MS. It’s also starting to affect my ability to draw as my hand has a tremor. I can still draw if I hold my pencil really tight but then my whole arm cramps up after a few minutes.

I’m taking a taoist approach to all this – do what I can when I can, don’t struggle against things I have no control over and try to keep my mind on a calm even path.

LikeLiked by 1 person

MS sounds a possibility, dreadful as it is, and a taoist approach — since it appeals to you, as it would do me — may well be the best way to cope with all this, mentally as well as physically. So sorry — thinking of it as a new chapter in my life might work for me and perhaps for you too?

LikeLike

Yes, I think you’re right – a new chapter is called for! New adventures await. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

♥

LikeLike

This is a fascinating post, thank you Chris, and I agree with the importance of first lines. My childhood Arthurian experience was chiefly the Lancelyn Green version but as a school librarian I discovered Kevin Crossley Holland’s The Seeing Stone which has, for me at least, a greater appeal. To my shame I have not read the Sutcliffe and should add that to my shelves.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I regret I’ve only read the first of the Crossley Holland trilogy, Anne, and that was after I’d published this essay in 2000. The Sutcliff is worth a read, a bit more literary and suitable for teens, and of course set in the Arthurian period rather the later medieval period. I could also have mentioned her Arthurian trilogy, but as I’d only read the second of the titles The Light Beyond the Forest: The Quest for the Holy Grail in a library copy I wasn’t able to quote from it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Incidentally, I’ve scheduled a review of Swan Song for tomorrow, it was every bit as good as you intimated.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m so glad that you rate it too. It’s a book that resonated with me, particularly as characters reminded me of people I know. It’s a kind book I think.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“A kind book” is a very considerate assessment, and I agree.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is a truly fascinating post and very useful too, as I am dealing with this subject in one of my classes. I’ll need to read it again. Thanks !

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re very welcome, Stefy, I’m pleased that it could be helpful for teaching purposes! 🙂

LikeLike