“To everything (turn, turn, turn)

There is a season (turn, turn, turn)

And a time to every purpose

Under heaven.”

As we drift past Imbolc and Candlemas, halfway points between the midwinter solstice and the spring equinox, I have been considering how season-centred some of my recent reading has been. And even my current read, Le Guin’s Malafrena, has so far been calibrated by principal periods of the year, especially the long hot summers and the winter feasts.

It might be an interesting exercise to consider how much fiction relies on not just space — and I’ll discuss this a bit more presently — but on the passage of time, especially certain liminal occasions; for, let’s face it, every moment is a liminal experience, balanced on a fulcrum of the present, between past and future, and frequently fraught with promise and danger.

In recent weeks I’ve posted reviews of novels which have featured the colder half of the year and associated chilly human attitudes — Barrie’s Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, Paul Gallico’s The Snow Goose, Sarah Perry’s Melmoth, and Joan Aiken’s Cold Shoulder Road. I’ve also included a couple of summer-set narratives, Wells’s The War of the Worlds dominated by fire and heat, and Lucy Boston’s The River at Green Knowe, in which high temperatures of August were moderated by cooling waters and pools. Whether I went deliberately for these contrasts I don’t now recall — perhaps I did it unconsciously — but either way it was pleasant to swap from one season to another.

But even more than seasonal contrasts I rejoice in the spaces with which fiction abounds. I don’t just mean the jumping between the orient and the occident that Salman Rushdie explored in his short story collection East, West — I’m thinking more particularly of the pretend lands that authors create as if they are themselves demiurges. To help me explore these territories I often resort to mapping — and coincidentally fellow blogger Nick Swarbrick only recently posted a piece specifically on this very topic.

Beginning with an appraisal of a map’s function he went on to discuss different audiences — the Reader, the Writer, and the Critic — and their responses. He then went on to ruminate on the map’s likely ethos and emotional qualities before talking about the relationship of the map with the text and with other illustrations which fictional works might include, giving copious examples from authors such as Tove Jansson, C S Lewis, Tolkien, Ursula Le Guin and a few modern children’s authors.

I myself habitually draw my own maps based on literary works where no maps exist or prove sketchy. Whether my efforts are diagrammatic or more cartographic they represent an attempt to place characters and actions in a landscape or urban environment, all part of an attempt to live as vicariously as possible in the environments described on paper.

Above is my attempt to relate the islands of the Dream Archipelago in Christopher Priest’s The Gradual to each other in terms of distance and travel times.

In the 70s I was inspired by Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels to make a sketch map for Tom’s travels in Charles Kingsley’s children’s classic The Water-Babies.

The illustration above shows the order of stations and branch lines of the Wetlands Express in Joan Aiken’s Midwinter Nightingale, expressed schematically; below, meanwhile, is a sketch plan of the Otherland Priory from the same Wolves Chronicle.

Some maps attempt a bird’s eye view of an area such as a cityscape.

No map was provided for the city state featured in The Malacian Tapestry by Brian Aldiss so in the 1980s I designed my own.

In John Masefield’s The Midnight Folk I based my rail map on part of the Welsh Marches centred on Ledbury, the town where the author was brought up and here renamed Condicote.

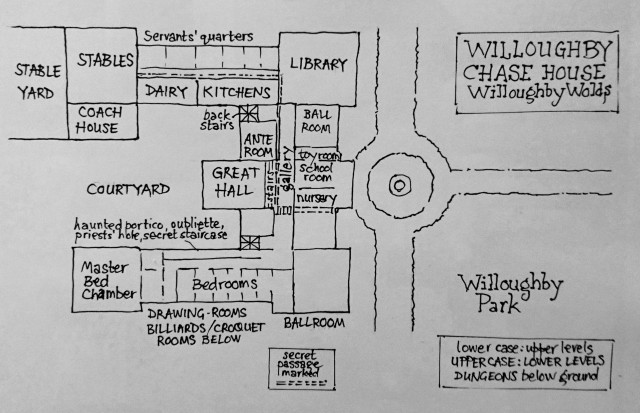

Returning to Joan Aiken’s Wolves Chronicles, I did a plan of Willoughby Chase House for a twitter readalong based on clues provided by the novel The Wolves of Willoughby Chase, and also a map of the mansion’s setting in a notional East Yorkshire, with Blastburn placed where our world’s Kingston-upon-Hull is located.

The young Brontë siblings were no mean slouches when it came to describing and mapping imaginary lands such as Gondal and Angria; Charlotte Brontë continued the habit in adulthood by basing the action of Shirley on an area of West Yorkshire she knew well, and I was encouraged to create a map to indicate the principal locations in her novel.

I believe we have a need to imagine and create landscapes which we can people with characters we want to love or hate. Indigenous Australians make their landscapes become vivid by narrating stories about key features in them, much as Europeans invest their countryside with folklore about heroes and giants and devils. For us moderns we have, as well as traditional maps, schematics such as sociograms, Venn diagrams and mind-maps which we use to envision the relationship between the individual and their surroundings.

The key word for me is vicarious, from an Indo-European root meaning a position in space (Latin vicus) and relating to a sense of substitution (as in vicar, a deputy). In fiction we may be encouraged to identify with principal characters or protagonists, and by such identification place ourselves, as it were, in their place. Naturally the next step is to follow them around in the story’s action, and for that we need maps.

All the foregoing has chimed in with my current read, Le Guin’s Malafrena, for which I’ve partly relied on the sketch map on the author’s website but which omits the copious cartographic detail which the text is constantly supplying.

While I await the arrival of The Complete Orsinia (which promises enhanced maps along with the texts and notes) I shall continue to build up my own map to follow Itale Sorde, Piera Valtorskar and Luisa Paludeskar as they traverse the length and breadth of their country through the seasons and years during a time of societal change.

“A time of love, a time of hate

A time of war, a time of peace

A time you may embrace

A time to refrain from embracing.”

— from ‘Turn, turn, turn’ by Pete Seeger (1959)

Do you have a similar attraction to fictional (or even factual) maps? Do you mentally inhabit the world they purport to represent or does the absence of a map worry you not one jot? Do you construct your own maps if the lack of one does concern you?

I found a note recently in an old diary which just says “I like maps in the front of books”. I think a map is a really lovely extra detail. For me I think it’s less about the map enhancing the experience while I read (a family tree is something I tend to find more practically useful), and more about extending the time I can spend with that story overall – for example, if I’ve finished the book but I don’t really want the story to end I can spend time looking at the map and remembering the significance of all the places. It gives a fiction extra presence in the world, besides the narrative.

I used to create fictional maps of my own, but I don’t remember ever having mapped a place from a book before. These ones you’ve created are really very lovely.

It’s a little while since I read a book with a map in, but my current novel, An Orchestra of Minorities by Chigozie Obioma, has some diagrams in the front to help explain Igbo cosmology. The narrator’s part of the spirit world so it’s been helpful to understand the terminology.

You’ve inspired me to create a map for a book this week. Not sure which book I’ll choose yet. As ever, thanks for sharing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That Chigozie Obioma work sounds fascinating because in my limited experience detailed mythic cosmology is not always easily conveyed in visual form as it’s often composed of complex symbolic interrelationships. Oh, and I also feel the need to draw up family trees and also socio grams, but maps come just a little higher in my priorities! Your desire for the story to continue by continuing to examine the map is one I relate to, for definite.

Glad you liked my maps, Isobel, and chuffed you’re inspired to do something similar for a book you’ve yet to choose! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love your literary maps, but then I love maps in general, but factual and fantastical. I haven’t drawn any maps based on a book but I’ve made plenty of maps of imaginary countries as a child and these days I regularly make GIS maps of various things for both work and pleasure. Last time I made a handrawn map was when I was about to move and wanted to map the town where I had lived but showing only the parts of it that I was actually familiar with.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think most of us have internalised mind maps of places we grew up in or currently inhabit or work in, don’t we: I know I have some for places I lived in during pre-teens years, going to secondary school, walking from campus to halls of residences in my uni years—none of these have I revisited in decades except in imagination.

Then there are those incidental maps we come across daily—train routes, the layout of hotel rooms in case of emergencies, outlets in a shopping mall, flow charts for office work, wordless flatpack furniture instructions…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Are you familiar with D M Cornish’s Monster Blood Tattoo trilogy? Some great maps therein, may suit you, sir.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wasn’t, but now I’ve looked them up (http://monsterbloodtattoo.blogspot.com/2008/02/evolution-of-map.html) I can see why they sprang to your mind, Michael. Also impressed with the costume designs and characters illustrated there!

LikeLike

I love these! I do love a literary map and your photographs are always stunning!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Cathy, and I’m especially pleased you appreciated the photos (Newgale beach in Pembrokeshire, the other from our bedroom window looking towards the Black Mountains)!

LikeLike

I can remember opening library books at random, looking for maps on the inside front cover. Odd thing to base your book selection upon, but it seemed to satisfy something in me.

I could use a map of Basho’s journey to the north in my current reading. I shall do a search.

LikeLike

Pulling some story books at random off my shelves I can see that, as well as R L Stevenson’s and Tolkien’s works, my editions of Gulliver’s Travels, The Wind and the Willows, Garth Nix’s Sabriel, Robin Hobbs’ Assassin’s Apprentice and James Branch Cabell’s The Cream of the Jest all have map frontispieces. I’m with you, Deb, many of my book selections were and remain cartographic choices.

Not read the Basho work but there’s something wonderful about plotting a real or fictional journey which, like those animated charts you see as a plane passenger, allow you to forestall the perennial question, “Are we there yet?”

LikeLike

Oh gorgeous! (Mind you, you had me at maps…) One of my favourite books is “An Atlas of Fantasy”, and any book which comes with a map has my vote!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I just had a look at the contents of An Atlas of Fantasy and it looks tempting, but I already have a 1980 edition of The Dictionary of Imaginary Places which includes copious descriptions and at least as many maps as your Atlas, so I may save my pennies for now!

I’m thinking of doing an annotated book list of atlases I’ve found inspirational, do you think that’d appeal?

LikeLike

It’s a lovely book I’ve had for about 40 years, so I’m very fond of it! As for a list, that sounds good. I like lists too…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Okay, that’s settled!

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a fascinating post, Chris. Since childhood I have loved maps and can spend ages poring over them. Literary maps are a particular joy and add so much to a book for me. Your plans linked to the Willoughby read along were so helpful and it’s lovely to see them again. Last February, I visited the Talking Maps exhibition at Oxford and imagine you would have enjoyed that too. https://visit.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/exhibition/talking-maps

LikeLiked by 1 person

I watched a couple of the videos attached to that Bodleian link, Anne, and yes, I would’ve enjoyed it—just a shame a certain global emergency reduced my opportunity to visit!

I’m glad you liked seeing my Willoughby plans again; I’m working on maps for the penultimate Wolves chronicle now! And I’ve a few more thoughts on maps in preparation for a future post—they aren’t ever far from my thoughts. 😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

I managed to sneak into the exhibition just before everything stopped!

I’m looking forward to reading more about maps soon ☺️

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lucky you, I’m envious! Now putting together some more stuff about maps and mapping…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Staggering and faraway from any capacity I may have. Can but look, read and admire.

LikeLiked by 1 person

In my case it’s less a skill and more an obsession with which to inflict on any wight who happens to be around! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your maps are fascinating, as are all their different styles. You have an enviable skill, Chris, of converting words into images. When I needed a map for my books I had to find someone else to make it for me. All my descriptions and distances were plausible and internally consistent but translating them into a map was beyond me. The final map was wonderful, however.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I remember seeing that map, really beautiful and impressive, and having just checked your blog see it was by Douglas Reed—you must’ve been been really pleased at how sensitive and technically brilliant a job he’d done. Beside that, my efforts are more sketches on the back on the back of envelope! But thank you. 😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

I really enjoyed seeing your maps, especially the map for “The Malacian Tapestry”. Super!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Jo, they’re not a patch on your images but I enjoy doing them anyway! I want to reread The Malacian Tapestry soon but I’m enjoying Le Guin’s Malafrena so much I’ll probably let that magic linger a bit; it’s worth a read if you can access a copy, especially for the weird Tiepolo engravings Aldiss used for inspiration.

LikeLike

Thanks, I’ll have a look at Malafrenna!

LikeLiked by 1 person

A really lovely post and thanks for the link to Nicktomjoe, I too have the need to map out the fictional places I’m visiting – very helpful when you’re imaging them all walking from house to shop etc! but just scribbles your maps are inspiring!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Really pleased you liked this, Jane, and good to know of a fellow map-scribbler! I have a post scheduled which refers to cognitive maps (among other things) which might resonate with you too. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person