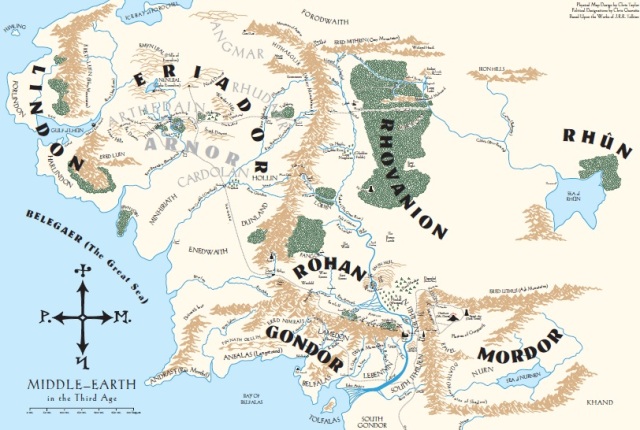

http://www.ititches.com/middleearth/me.pdf

In ‘Where was The Shire?’ I mentioned a tradition, local to the Vale of Usk, claiming that Tolkien had not only written part of The Lord of the Rings in Talybont-on-Usk, Powys, Wales but also based his notion of The Shire — the hobbit homeland — on aspects of the Black Mountains landscape. Huge questions and objections had loomed large in my mind however, and it soon became clear that I wasn’t not alone in doubting the likelihood of this recent ‘tradition’. I then promised a follow-up post, and here it is.

Nikki from Bibliophibian Inc. suggested I have a look at Tolkien’s letters, and this was one of my first ports of call (Carpenter and Tolkien 1981). Two online sources (http://www.visitwales.com and http://www.bucklandhall.co.uk) both state categorically that Tolkien either definitely or “apparently” stayed in Talybont during the 40s. That’s a long decade, the first half dominated by the war of course. By the time war was declared on 3rd September 1939 Tolkien had taken his hobbits beyond the Shire, indeed they’d already moved on from Rivendell. As I’ve previously established, if the Buckland and Crickhollow of The Lord of the Rings really were inspired by the Buckland and Crickhowell of the Usk valley then it happened before the forties.

Still, did Tolkien indeed spend time at Talybont-on-Usk in the forties? Do Tolkien’s letters written at this period refer to an extended visit here? The simple answer is, as you might expect, no. From March 1940 (letter 38 in The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien) to December 1949 (letter 122) no correspondence that notes where Tolkien was then residing indicates Wales as his location — though, to be fair, only his Oxford home addresses, Northmoor Road and Manor Road, and Merton College are ever referenced. Of course, absence of evidence is not evidence of absence; but given that during the war years Tolkien’s time was taken up with onerous university duties and, at least during 1942 and 1943, work as an air-raid warden, it seems unlikely that he had any free extended time to travel, even across to Wales. Nothing in the extant letters to his sons, acquaintances, colleagues or publishers hints at any such sojourn between 1939 and 1945.

A letter (numbered 47 in The Letters) to his publisher Stanley Unwin in late 1942 claimed that in intervals afforded by academic work and ‘Civil Defence’ The Lord of the Rings was “approaching completion”; in truth, it wasn’t until Summer 1948 that he was able to write that he’d “succeeded at last in bringing the ‘Lord of the Rings’ [sic] to a successful conclusion.” Through most of 1949 he finalises The Lord of the Rings, making corrections as he types up this last draft. Did he then spend time in Wales in the four years after the war when the epic was being completed?

Again, I can find no direct evidence in the Letters, though there are one or two possibilities. To complete The Lord of the Rings he wrote that he had managed to “go into ‘retreat’ in the summer” of 1948, but doesn’t say where he’d ‘retreated’ to (letter 117); in February 1949 (letter 119) he writes that “after 25 years service I am shortly going to be granted a term of ‘sabbatical’ leave, partly on medical grounds,” and this is when he types out his fair copy. Theoretically — and in the absence of any corroborative evidence — either of these two periods could have seen him in Talybont, but I am dubious.

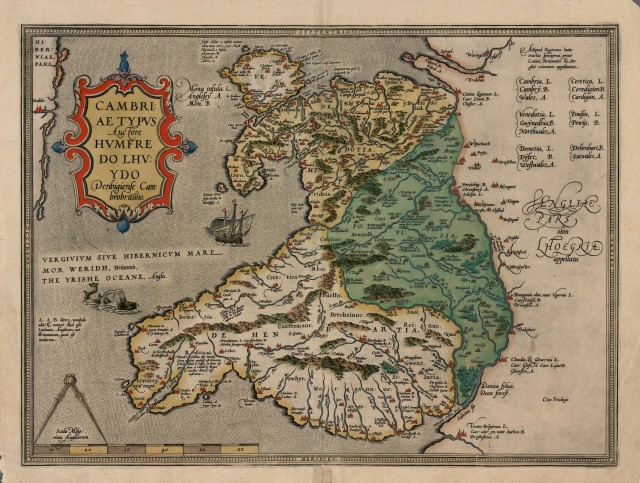

I next looked at Tolkien’s well-known fascination with Welsh. A lecture given at Oxford in 1955 was first published as ‘English and Welsh’ in 1963 and subsequently republished in The Monster and the Critics and Other Essays in 1983. I read this a few years ago, and in refreshing my acquaintance with it find that memory serves me right: at no point does he acknowledge experiencing Welsh in anything other than in an academic context. This is not a criticism but an observation on a lecture given to a scholarly audience. The closest he admits to first-hand contact with everyday Welsh is on coal-trucks marked with placenames, railway station signs, a house inscription declaring it was adeiladwyd 1887 (“built 1887”), all presumably from one or more holiday trips to places far to the west.

That Tolkien visited Wales at some stage seemed undeniable to me; but when? And where? Professor Carl Phelpstead, author of Tolkien and Wales: Language, Literature and Identity (University of Wales Press), very kindly replied to my request for any details. With the caveat that, following his book’s publication in 2011 he’s not kept up with more recent work in this area, he confirms that as far as he knows there is no evidence that Tolkien stayed at Talybont.

I have looked again at my book, and the only visits to Wales for which I could find evidence when I wrote the book are as follows: a summer holiday in Llanbedrog in North Wales in 1920, a drive to the Black Mountains while staying with George Sayer in Malvern in 1952 (when he could, I suppose, have visited Talybont and Criccieth [a slip for Crickhowell] — but I know of no record that he stayed in either), a few visits to Aberystwyth to serve as external examiner there, and journeys through Wales to catch ferries to Ireland. The 1952 visit would, of course, be too late to have influenced [The Lord of the Rings].

So Tolkien’s 1955 memory of coal-trucks and railway stations was possibly from 1920, when he was in his late twenties. But his fascination with Welsh predates that: when he was still a student in Oxford, before he joined up in 1916 to fight in the trenches, he won the Skeat Prize for English at Exeter College, spending some of the money on a Welsh language book: J Morris-Jones’ A Welsh Grammar Historical and Comparative: Phonology and Accidence (1913). And, as cited in his 1955 lecture, Tolkien had a facsimile copy of Wyllyam Salesbury’s 16th-century Dictionary in Englysshe and Welshe which he had acquired in 1907, aged around 15.

With regard to Talybont Professor Phelpstead concedes that

It is quite possible that he also visited at other times, but when writing my book I read everything I could find that might shed light on Tolkien’s relations with Wales, its language, and its literature, and I came across no reference to his staying in Talybont. The fact that the exhaustive biographical information collected in Hammond and Scull’s J. R. R. Tolkien Companion and Guide: Chronology includes no mention of a stay there suggests there is almost certainly no documentation of such a visit — certainly nothing known to Tolkien scholars.

After only just a little digging we seem to have reached a rather negative conclusion: all the claims pertaining to Tolkien staying at Talybont in the 1940s to write The Lord of the Rings are uncorroborated. But there are some interesting true facts to be drawn from all this, as opposed to the ‘alternative facts’ of the Talybont visit.

- First, Tolkien had a longstanding engagement with the written Welsh language, from at least his teens when he acquired a copy of Salesbury’s Dictionary.

- He retained strong aural memories of his 1920 visit to Llanbedrog in the Llŷn peninsula, to the extent of remembering the pronunciation of individual Welsh words (such as that for oxen, subsequently noting it in the pages of his Skeat Prize Welsh grammar).

- He used some of the linguistic characteristics of Welsh (such as mutation) to model at least one of the Elvish languages, Sindarin, of his Middle Earth legendarium.

- His deep interest in and knowledge of philology extended to placenames, whether or not he had actually visited them in person. Even if he only been to the Black Mountains as late as 1952 — in company with George Sayer, senior English master at Malvern College and later biographer of C S Lewis — he was perfectly capable of visiting them in imagination or on a map, where he could have borrowed, if indeed he did, the placenames of Buckland and Hay, and Crickhowell as Crickhollow.

I need only draw your attention to Farmer Giles of Ham, which was published in 1949, to illustrate how like any good author Tolkien chose to be magpie-like in selecting whatever suited the material he was working on. In Tolkien’s imagination Wales was a place of wonder, a land where giants and dragons dwelt to periodically assail the lowlands of England. In Farmer Giles the “midmost parts of the Island of Britain” rarely gave thought to the Wide World.

But the Wide World was there. The forest was not far off, and away west and north were the Wild Hills, and the dubious marches of the mountain-country. And among other things still at large there were giants …

The Wild Hills are the mountains of Snowdonia — we know this because when the dragon Chrysophylax returned to his lair he had to rout out a young dragon, and it was said that “the noise of the battle was heard throughout Venedotia” or, as we know it, Gwynedd. In 1920 Tolkien would have seen these mountains from Llanbedrog. In Farmer Giles the author was clearly drawing on his own memories and experiences of Wales, for which we have documentary evidence.

Unfortunately, when it comes to Buckland and Crickhollow in The Lord of the Rings all we have is an ignis fatuus, a will-o’-the-wisp of a connection.

Select references

Humphrey Carpenter and Christopher Tolkien, Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien. George Allen & Unwin, 1981

Barbara Strachey, Journeys of Frodo. Unwin Paperbacks, 1981

J R R Tolkien and Christopher Tolkien, The Monsters and the Critics and Other Essays. HarperCollins, 1997 (1983)

J R R Tolkien and Christopher Tolkien, The History of the Lords of the Rings, Part One: The Return of the Shadow. Unwin Paperbacks, 1990 (1988)

J R R Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings. HarperCollins, 1993 (1968)

Tolkien’s invented languages

Dimitra Fimi “Researching Tolkien’s ‘Secret Vice’” June 29, 2016

http://dimitrafimi.com/researching-tolkiens-secret-vice/ [accessed March 14, 2017]

Very interesting, your research skills are second to none! 🙂 Is there a grand plan to your investigation? Or do you just go where the curiosity takes you? You have such focus and attention to detail.

Also, what does ‘mutation’ mean? You say Welsh has it.

LikeLike

You’re much too kind, Petra, but thank you! This is only — I hope — the culmination of solving a little niggle I had after moving to Crickhowell in the Black Mountains of Wales: the question of whether this area was really “Tolkien’s Shire” as local lore seem to have it. The more I looked at the claim the more it seemed like a chimaera or will-o’-the-wisp; and now it’s virtually faded to nothing in the cold light of day.

The only loose end is the mysterious character “Fred from Tredegar” who is supposed to have inspired the individual Fredegar (“Fatty”) Bolger in The Lord of the Rings. Unless he’s a friend of George Sayer, Tolkien’s connection in the Malvern Hills, I’m inclined he’s a mischievous invention.

Ah, initial mutation. One of the bugbears of dysgwyr cymraeg or Welsh learners! An excellent example is when you need to describe being “in Cardiff”, the capital of Wales. Yn is Welsh for “in” and Caerdydd is Cardiff, so you’d think yn + Caerdydd would be the obvious solution — but you’d be wrong! It’s yng Nghaerdydd …

See what I mean? And this is, I understand, a feature of Sindarin, one of Tolkien’s Elvish languages; so you won’t be surprised that despite my inherent nerdiness I’m disinclined to learn it, pretty much the reason I’ve only got so far in learning Welsh. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah yes, tricky. I struggle enough with the human languages, to be ready to move onto Elvish. I hope that sometime soon I’ll be able to download languages into my brain, I’ll get Elvish as part of a whole package then 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’d be nice to download Elvish, certainly, but myself I’d have to delete Selfish to make room on my grey matter hard drive, I think!

LikeLiked by 1 person

😀 !

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent post Chris, I thoroughly enjoyed reading it. ‘ink biotic’, mutation is the single facet of the Welsh language guaranteed to drive the learner crazy – the changing of the initial letter or sound of a word based on various grammatical rules (I hope that’s an accurate description, as a learner, that was always my impression). It can cause havoc when trying to use a Welsh / English dictionary 🙂 .

LikeLike

Glad you enjoyed this, Dale, I hope I’ve got this bug out of my system now! And thanks for the reblog, I’m always gratified that you think enough of my musings to share them. 🙂

I gave an answer of sorts to Petra about mutation, but your response was much more succinct! And you’re absolutely right about the difficulties of navigating around a Welsh-English dictionary when you have to remember the rules, and when the mutations themselves vary so much depending on context.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Cheers.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Tolkien ap Azard – Earth Balm Music

Fascinating, Chris, how the Shire has been so closely linked to Wales with hardly a shred of concrete evidence- but such is the way that myth grows!

Your research is fascinating and exhaustive, it seems to me at least.

I didn’t know that about the Welsh language, that initial letters sometimes change due to context and so on – that is tough on any non native trying to learn it. Great post as always

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Lynn! I don’t know about “fascinating and exhaustive” but I certainly had fun researching it, and was exhausted after trying to get a coherent narrative out of it all!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Haha! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah, the joys of esoterica. The academic in me is deep in admiration of your skills, and the lazy bum is deep in awe of your energy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re too kind, Lizzie, but I am no true academic, merely an inveterate picker-up of trifles (a phrase, by the bye, that I’ve half-inched from some writer or other). In truth I’m that lazy bum whereof you speak, leaping into brief action when a will-o’-the-wisp catches my fancy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Proposal for dissertation: I inspiration – Eleonora Laddago: Anim Year 3