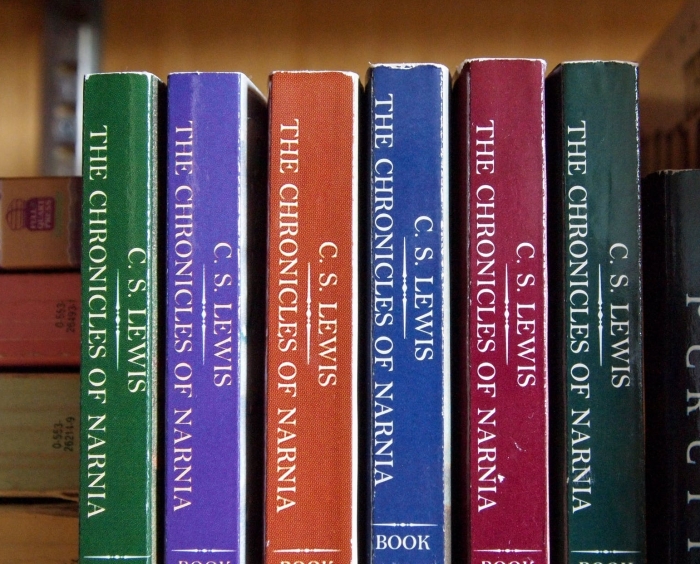

As I promised in a previous post I shall be examining the taint of alleged racism that C S Lewis’s The Horse and His Boy has acquired, and ascertaining if it’s justified. I also promised to look at the planetary aspect by which this novel is ruled, according to Michael Ward’s Planet Narnia, namely Mercury, which seems to go towards determining Lewis’s overall schema for the Narniad.

But I shall start by also briefly (?) mentioning novels that reveal a glancing relationship with some of this novel’s characteristics.

Note that there’ll be spoilers. Also that most links here will take you to one of my reviews or threads. And now, farther up and farther in!

Related fiction

First is Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, particularly the second of two parts that were published in the same year as Lewis’s title. The Two Towers (1954) has a siege at a climax, as does The Horse and His Boy. Though the respective atmospheres could hardly have been different it’s a delightful coincidence that both former Inklings featured citadels menaced by outside forces, and that both Helm’s Deep and Anvard were relieved by friendly armies turning the tide of war.

Another three contrasting fantasies follow. Joan Aiken’s The Whispering Mountain (1968) is an alternative history set in early 19th-century Wales. In this appears a young adult called not Aravis but Arabis. I don’t know where Lewis got the name Aravis for his protagonist from, but the word ‘arabis’ refers to an alpine plant, and thus an apt name for a character in a novel about a mountain; the Welsh word arabus, which is pronounced exactly the same, means ‘witty’. I wonder if Arabis was a subconscious memory of Lewis’s protagonist; however, when once asked what she thought of Lewis’s Narnia books Aiken replied,

I can’t stand them actually. My daughter [Lizza] was very addicted to them, she loved them all, but I prefer his books for adults. […] The children’s books are great adventure stories—but there’s something slightly prissy, and talking down; and the Christian message drummed home. And I just don’t like that great big golden lion.

Wintle and Fisher 1974:166

So that’s that… This leaves – where this short discussion is concerned – Philip Pullman and Lev Grossman, both of whom have in different ways more or less explicitly critiqued Lewis while at the same time happily drawing on aspects and elements of the Narnia books.

Critic Sam Leith saw Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials series as a kind of “anti-Narnia” while Pullman thought Narnia itself “wicked”. The author found the stories “very dodgy and unpleasant – dodgy in the dishonest rhetoric way – and unpleasant because they seem to embody a world view that takes for granted things like racism, misogyny and a profound cultural conservatism that is utterly unexamined.” He wasn’t alone: Alan Garner recently declared he could never read the Narnia chronicles again: “They were, and remain, nasty, manipulative, morbid, misanthropic, hectoring, totalitarian and atrociously written.”

Pullman’s own dislike though wasn’t absolute, as statements in his essay collection Dæmon Voices indicate. But antipathy to Narnia didn’t stop him also having his own protagonists Lyra and Will visit parallel worlds, or transforming Lewis’s talking animals into dæmons, introducing a wardrobe in the opening scenes of Northern Lights (when Lyra sees Cittàgazze for the first time) and describing mythical creatures like angels and fairies (the latter called Gallivespians, with spurs as dangerous as the stings of gall wasps, the insects from which they may have taken their name). Lyra, you’ll have noted, rides the talking bear Iorek Byrnison whereas Shasta rides the voluble horse Bree.

Meanwhile, Lev Grossman’s Magicians trilogy (The Magicians and The Magician King, followed by The Magician’s Land) is centred on a parallel world which, though seemingly described by an author called Christopher Plover as fictional in a series of novels (‘Fillory and Further’) really turns out to be accessible by college students using magic. Grossman, a fan of the series though no Christian, set out to write an adult series riffing on Lewis’s Narnia while throwing in elements inspired by, among others, J K Rowling and Donna Tartt: his Neitherlands, for example, is a mix of the deserted city Charn and the Wood between the Worlds from The Magician’s Nephew, while an expedition eastwards by sea is a clear reference to The Voyage of the Dawn Treader.

As for The Horse and His Boy, there is an appearance right at the end of the third Magicians book of the so-called Cozy Horse, a creature reputed to be one hundred feet high and covered with a velveteen skin. In the novel we’re told it originally featured in the Fillory and Further series, and as well as being vaguely reminiscent of the Trojan Horse it’s clearly both a homage to and a distortion of Shasta’s mount Bree:

It was easily the silliest single inhabitant of Fillory, a total nursery fantasy [. …] “But what’s it doing here?’ The Cozy Horse regarded them dumbly. It wasn’t going to tell. It flared its nostrils and gazed off over their heads in that supremely unconcerned way horses have.

Chapter 31, ‘The Magician’s Land’

Quicksilver

Critics have long wondered what Lewis’s overarching schema for the Chronicles might have been. Michael Ward argued, very plausibly, that if each of the Narniad titles fell under one of the seven medieval planets (which included the Sun and the Moon) then The Horse and His Boy would’ve been symbolised by Mercury. The real planet is, with a year lasting only 88 days, the quickest planet round the sun and therefore the embodiment of the messenger of the gods, Hermes or Mercury; unsurprisingly the novel is about the horses Bree and Hwin who together characterise speed.

Maybe they are meant as Narnian equivalents of Arab steeds. But we also mustn’t forget that a large chunk of the novel is about getting a message to the king of Archenland warning that Rabadash is about to invade the country, another echo of the role that Hermes assumed.

But mercury is also the fluid element commonly known as quicksilver, once used as the reflecting material in glass mirrors. This accounts for the frequent mention in the novel of pools, springs and streams being reflective; it’s even hinted at in the galleon with swan’s head prow and carved swan’s wings, the Splendour Hyaline in which the Pevensies sail swiftly to and from Tashbaan. “Hyaline” means glassy or translucent, and in poetry often describes a smooth sea or a clear sky, one mirroring the other.

So with at least those three qualities – swiftness, the conveying of messages, reflectiveness – it’s more than possible to credit The Horse and His Boy with being under the aegis of Mercury, I agree.

Prejudices

Now we come to the frequent accusations of racism and cultural appropriation in The Horse and His Boy. Lewis is obviously referencing historical Levantine and Western Asian culture in his descriptions of the Calormenes as dark-skinned and wearing turbans, sporting footwear with upturned toes, wielding scimitars, and speaking and acting in a stylised way adapted from translations of the Arabian Nights (such as that by the oriental scholar Sir Richard F Burton). Further, their nobles – Tarkaans and Tarkheenas – derive their titles from the Central Asian term tarkhan and their coins moreover are called crescents. Given that many of the male figures – Arsheesh, Anradin, the Vizier, the Tisroc and Rabadash – are portrayed as power-hungry and cruel, it’s easy to gauge that Lewis may have been displaying his prejudice against a whole culture.

But let’s examine the details of that charge sheet, namely in terms of stereotyping, slander or calumny, and Lewis’s own prejudices.

Stereotyping. It’s clear that Lewis was borrowing much that pertained to Calormen from the Arabian Nights. Whether in the bowdlerised versions for youngsters or the dense unexpurgated translations that began to appear in the 18th century we can see that characterisations and descriptions were such that us moderns might well flinch when reading now. In ‘The Story of King Shahryar and His Brother’ which sets up the Scheherazade frame story we read for example of the King’s brother’s wife sleeping with a black cook, the pair murdered by being quartered by the brother with a scimitar before they wake, then the brother seeing the King’s wife sleeping with a “slobbering blackamoor”. The appalling misogyny and racism, along with summary executions, all set the tone for many of the remaining tales.

But, crucially, they didn’t set the tone for Lewis’s novel. Daniel Whyte makes the point very well – better than I can – and as a person of colour he would personally be on the alert for any suggestion of racism in the narrative: Lewis is on the side of Narnia, he says, so enemies of Narnia, whatever the colour of their skin, will always have mean motivations and actions attributed to them. Nor is Lewis anti-Islamic: the Calormenes worship any number of gods but principally Tash, a figure so unlike Allah that no-one would seriously suggest they’re one and the same.

Calumny. The stereotypes of wicked uncle figures, wily viziers, cunning caliphs and duplicitous djinns are also endemic in the Arabian Nights, and while he’s toned down much of their characteristics Lewis has no compunction in drafting them into this fiction. Was he casting aspersions on the peoples of Western Asia in his depiction of the Calormene villains or merely aping his models? Just as he purloined tropes and motifs from medieval European romances for previous episodes such as Prince Caspian (which had their own despicable villains) he may have treated different sources in the same way for The Horse and His Boy. Unlike most of the male characters, however, the females – Aravis and Lasaraleen, principally – are presented more favourably and with more nuance, like some of the strong female roles in the Arabian Nights (beginning with Scheherazade herself).

Prejudice. I think it’s hard to deny that Lewis was prejudiced – as indeed are we all to a greater or lesser extent. Certainly he will have entertained preferences for Northern European cultures: and from the books think of the battle cry “Narnia and the North!” and the many statements that Narnia had a better society than Calormen, that Shasta was intrinsically better than his Calormene contemporaries, that Narnians were way less wicked than Calormenes, the giants of the far North or the Telmarines (until they were assimilated with the Narnians).

However, he wasn’t an insensitive man: we are reminded that although an Anglican he married a Jewish divorcee, suggesting that in religious matters it’d be foolish to accuse him of bigotry; and he always felt an outsider amongst English academics on account of his middle-class Belfast origins, so he knew how it felt to be regarded as somehow different, and not “one of us”. Whyte’s criticism of Lewis’s sensitivity is quite nuanced:

“Perhaps a writer more sensitive to the times, or more cosmopolitan in his outlook, would have considered that people outside of the English and Western European cultural arena might one day read his books and he would have been more meticulous and objective about his world-building. But Lewis was no Tolkien when it came to world-building and tossed in whatever he liked as he went along.”

Whyte 2021

Now I’m not setting myself up as an apologist for Lewis. In terms of his portrayal of Calormene peoples and culture we can, even allowing for the transitional post-imperial period he was living in, deduce with some justification that in this novel he could be described as tone-deaf. We may therefore wish he’d avoided outright comparisons with Islamic cultures and steered clear of hackneyed clichés: self-deprecation would’ve been better.

Richard F Burton, translator, Jack Zipes, adapter. 1997. Arabian Nights, A Selection. Penguin Popular Classics.

Lev Grossman. 2014. The Magician’s Land. Arrow Books, 2015.

Michael Ward. 2008. Planet Narnia: The Seven Heavens in the Imagination of C. S. Lewis. OUP.

Daniel Whyte IV. 2021. ‘There Are No Cruel Narnians: What The Horse and His Boy Can Tell Us About Racism, Cultural Superiority, Beauty Standards, and Inclusiveness.’ A Pilgrim in Narnia.

https://apilgriminnarnia.com/2021/09/15/narnia-and-race-whyte/

Justin Wintle and Emma Fisher. 1974. The Pied Pipers. Interviews with the influential creators of children’s literature. Paddington Press.

Interesting, thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pleased it piqued your interest, Liz. 🙂

LikeLike

On the stereotypes, I think you are right, I hadn’t considered ones part of the Arabian Nights (I don’t think I’ve actually read a full version of these–probably just a kiddie version as a child)–but I do agree on the wicked viziers, the constant plotting, marriages to older and not appropriate grooms as as much elements in eastern tales.

As to his prejudice, what interested me was how it extended to even food and poetry 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve only read a couple of Burton’s Victorian translations – like you my memories are mostly of bowdlerised adaptations as consumption for children – but they’re mostly turgid and non-PC for a modern reader. I think we agree there’ll have been some prejudice, common for the period, embedded in the text and that we don’t have to condone that these days if we’re in any way sensitive to these issues!

LikeLike

Thanks for this, Chris – and what a wonderful word is ‘hyaline’!

Incidentally, Mercury is the ruler of the sign of Gemini, ‘the twins’, which seems kind of appropriate for The Horse and his Boy!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I saw the Mercury / Gemini connection mentioned somewhere or other, but as I’m not particularly au fait with astrology I thought I’d leave it up to cognoscenti to make the link! I’d be more interested in NASA following up their Mercury missions in the 60s with their two-man missions … Gemini.

And yes, hyaline, eminently a very Lewisian word I fancy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

First time I’ve ever been numbered amongst the cognoscenti!

LikeLiked by 1 person

If you can pronounce the word correctly you’re in! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I can’t do emojis on here from the PC but if I could it would be one of those falling around laughing ones! (Having just used up 22 words, I can see the point of emojis!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Whoops – wrong WordPress account!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hah, no worries! 😁

LikeLiked by 1 person

Using any keyboard on WordPress I think you can do a limited amount of emojis – for instance a smiley face would be a colon symbol : followed immediately by a close bracket ) with a space before and after the two 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the emoji-making tip, Chris … And now you know my secret identity! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lips sealed and all that! 😁

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating as ever, Chris. Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks,. Sandra, I’m so pleased I was bumped into doing this Narniathon – I knew I’d get more out of the Narniad on a second read but wasn’t prepared for how much.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting, Chris, and thank you for your measured thoughts on the prejudices (or not, depending on your viewpoint). I think tone-deaf is a good way to put it, and although I was aware of the things that wouldn’t be written now, they didn’t spoil the book. I feel I am able to apply context here as I’ve said in my various comments on Horse, which I did enjoy a lot more nowadays!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I did enjoy your take on TH&HB, Karen. On my part, I had the Pullman and Garner accusations in mind when rereading this, only to find it wasn’t as bad as I remembered it! What is it they say about second opinions?!

Still, I feel uncomfortable about white Europeans appropriating (even if done light-heartedly and non-judgementally) material from another culture in a way which could so easily be badly misconstrued. One of Diana Wynne Jones’s stories does something similar (https://wp.me/p2oNj1-8r) which I don’t think quite works.Then there’s Vathek which muscled in on the original Arabian Nights mania – which I’ve yet to read –.so where do we draw the line? Mozart’s ‘Abduction from the Seraglio’ did something similar with a scenario from Ottoman Turkey…

LikeLiked by 1 person

I find your arguments for and against interesting and compelling. I struggle with the idea that every book ever written has to be held up to the light nearly seventy years later to see if it holds up to today’s sensibilities. Hence, I still believe in reading To Kill a Mockingbird and The Adventures of Huck Finn, even though they do not conform to today’s standards of racial fairness. But then we need balance and discussion in our reading choices, too. It is a tough situation for us readers. Do we abandon our old favorite series because of what we know now? I am very muddled on the subject.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know how you must feel, Anne – and must we always hedge around our reviews and discussion of ‘difficult’ works with caveats? But it’s always about context, isn’t it, which’ll always be a moveable feast: certain classics were badly received at the time which now we rave about, while others – lauded or laden with prizes – have fallen into justifiable obscurity.

We bring to each work our own viewpoints, our prejudices, and our sensibilities, and that’s as it should be – provided we don’t hurt anybody. But that doesn’t mean that what we say mayn’t offend some, because that’s inevitable. For myself, I try hard to focus on whatever virtues something has more than its vices, a habit that many years of teaching has inculcated in me!

LikeLike

Another fascinating and balanced post, Chris. Your points regarding the racism in particular struck me as I think it’s important to remember Lewis’s own background and the attitudes prevailing at the time.

I’m also starting to come round to the idea of the planetary links given the convincing argument you make. Thanks again and by the way I’m enjoying re-reading The Magician’s Nephew at the moment!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I saw the mention of The Magician’s Nephew in your post, so I’m chuffed you’re enjoying it! I’m also pleased you think my observations on racism and planetary links make sense – it’s always reassuring when my instincts as well as reasoning resonate with others! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think Tash is drawn from the gods and idols that play such a large role in the Old Testament. Calormene seems a mix-up of these two literary sources, the Arabian Knights and the Hebrew Bible, plus a dash of the medieval Crusades.

It’s generous to point out enemies of Narnia can be any skin color, and fairly true, although the Calormenes in the two books in which they feature as enemies are quite overwhelmingly dark. Plus, it is a fact that Lewis characterized Narnians as “white.” If only he hadn’t done that. (On the other hand, who could be whiter than the White Witch, the ultimate enemy?)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, you’re right, Lory, there’s no end of pagan gods mentioned in the OT – just from the top of my head I can think of Baal,.Marduk, Tammuz, Dagon, Ammon, not forgetting the odd golden calf – luckily Tash isn’t among them! I didn’t get a hint of any invading crusaders though, just the defenders in Anvard plus various denizens of Narnia.

I still see Lewis’s depiction of Calormenes as problematic, though my view is more nuanced than when I first read this instalment and, White Witch notwithstanding, less – erm – black and white.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Crusade flavor is more of a general medieval vibe, not that Narnians are bent on crusades against other nations that don’t know Aslan — and thank goodness they are not, just think how much more distasteful that would be! The fact that Calormenes are portrayed as bent upon invasion and imposing their religion on others (which gets accomplished in the last book) is clearly seen as about the worst thing a nation or group of people can do. Which is rather interesting, actually.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Invasion “the worst thing a nation or group of people can do”? As true now as it ever was.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“Pullman thought Narnia itself “wicked”…”. that’s rich! Perhaps Philip wasn’t aware of his own work?😉 I suggest that Philip Pullman “sees through a glass darkly,” even more so than most of us.

The beauty of C. S. Lewis’ work, for me, is bringing fresh insight into the Lion. Even reading this now, at such a late stage in my Christianity, I think, “Aslan couldn’t have been the one who struck Aravis!” and yet, it was so. His ways are not our ways, and surely each of us could do with some refining. I know that I need much…

As for prejudice…I think that has become a popular buzzword lately, taken out of proportion to what the authors intended in their writing. Did Barrie mean to disparage the Native Americans when Peter Pan went to their island? Hardly! Or, at least not any more than we did as children when we played Cowboys and Indians, or my high school alma mater which was the Redskin. How proud I was when the Chief, our mascot, would come ahead of the band down the center of the football field with his headdress almost touching the ground as he danced. Now, they are called the RedHawks, which I think is just plain silly. It has none of the nobility of the fierce and proud Indian.

Well, you can see I have no shortage of opinions. But, it is a delight to reread the Chronicles with you, and share in their Story. (Capital S intended.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

p.s. Now that I think about it, I suggest he intended to portray conflict with the Calormenes and their faith. Weren’t the Ishmaelites/Muslims against God’s chosen people, the Israelites, meaning to “destroy them as a nation, that the name of Israel be remembered no more”? (Psalm 83:4) Surely there was conflict there, just as Lewis portrayed with the Calormenes.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have to say that I profoundly disagree with this interpretation. As an historian I don’t believe that the Psalms, the latest of which are at least two and a half thousand years old, can be used to denigrate Islam, which had its origins a millennium later. The psalmist would have been inveighing against contemporary enemies even if poetically he was looking to the future of the kingdom of Israel.

The problem with ascribing prophecy, indeed relevance, to events far distant in time is that it’s a two-edged sword: the kind of curse that was drawn down on the Jews themselves when the Gospel account of the crowd shouting “His blood be upon us and on our children” was interpreted as licence to persecute and murder anyone of the Jewish faith – the very Jews some Christians are happy to use the biblical texts of against them. (Note I’m not ascribing this attitude to you!)

I’m absolutely sure that Lewis, whose academic learning made him well aware of Islamic contributions to medieval science and literature, would not have intended TH&HB to be an anti-Islamic diatribe, any more than the other books would have denigrated the pagan worlds of Norse or Greek myth and legend for non-Christian beliefs.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree that C. S. Lewis did not intend his books to be a diatribe against Islam, absolutely. I’m only suggesting that some of the differences (and conflicts) between the Isrealites and the nations they encountered may also be represented in his books.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, I do see that, thank you, absolutely!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I smiled at Pullman’s reaction then, though I have to admit that when I first read all the Narnia books as an adult my reaction wasn’t too dissimilar! Now though I, and I suspect Pullman too, have a more nuanced view – though I come to it as an atheist while he leans more to agnosticism.

What the Lion (or deity, with or without a capital ‘D’) would or wouldn’t do, and their reasons for such acts, is I agree unknowable. This, I think, is my problem with theism: we are expected to love a deity as though they are human, but they reserve the right to act in unpredictable ways and we are encouraged to accept it. I know enough of the psychology of abusers and their victims to regard such relationships as suspect. (My partner is a psychologist, and we managed.after much heartache to get a family member away from just such a relationship.)

Prejudice, regardless of whether it’s a buzzword, has ever been with us over time. Prejudice can be a good or a bad thing depending on context and circumstances, experience or indoctrination, logic or emotion. That’s why we need to understand where, why, when and how prejudice arises, and indeed whether it is indeed prejudice, ignorance, social norms or whatever.

I’m being opinionated, I know, but I hope not overly doctrinaire! I am pleased so many readers are enjoying this revisit (or first visit) to Narnia, and even if we may disagree at times at least relish all that we enjoy in common about Lewis’s vision!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah, now that I understand that you are an atheist explains a lot. No wonder you do not apply the Psalms as I do, and please, I mean no disrespect whatsoever. We approach Narnia, and the Bible, from completely different perspectives: I come primarily from a position of faith, you come from a position of learning. However, C. S. Lewis embodies both quite well, which makes his books so effective. What a fascinating discussion to have with you, over this book alone. I wish we could be in the same room to discuss it, as friends, instead of typing away on keys.

It interests me that you chose to read all the Chronicles.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for such a generous reply! Actually the reason I’m rereading all the Chronicles (this time in publication order) is that I was gently ‘persuaded’ to run this Narniathon – though to be honest it didn’t take a lot of persuading! My first ever reaction to the complete Chronicles was to baulk at what I saw as its preachiness, but I knew there was more to it than that and that I would at some stage revisit Narnia.

And that’s the thing which you point out so well, Lewis embodies the Chronicles with both faith and learning, allowing the reader to take what they want and can from them. So if we agree to differ on some aspects I’m pleased that there’s more that we can actually agree on!

LikeLiked by 1 person

We all have hyaline cartilages in our body which make up structures that have to be both sturdy and flexible. Typically these structures are used to send and receive sound ie ear and larynx. It has been very thought provoking to read this post and all comments. Especially the last interchanges. Being aware of the different contexts from which we derive our opinions makes all the difference as does our physical presence to make immediate adjustments to our comments (along with the necessary gestures and tone of voice necessary to couch our words to elicit our intentions) This is my nod to emojis Always a challenge when writing

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks for commenting, I’m glad you found the post and the discussion interesting!

Yes, that’s the modern application of the term ‘hyaline’, isn’t it, though the derivation is from the Greek ὑάλινος (hualinos) meaning ‘glass’. I knew about this meaning before I became aware of the biological application.

And I agree that interaction online using text is not always the best of ways to communicate with subtlety and nuance or to encourage dialogue on an equal footing. (Even face to face dialogue can come a cropper if tones of voice or gestures are misinterpreted!)

I tend to use a limited range of emojis to express a joke being made, say, an appeasing attitude, that I agree or disagree with an opinion, or that I’m not sure about something – all, as you suggest, substitutes for things unspoken but conveyed in other ways.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Sunday Salon: A Book for The #1954 Club and a new limited edition Traveler’s Notebook – Dolce Bellezza

I’ve always been irritated with Philip Pullman’s vitriolic critiques of Lewis. To me it comes off as sour grapes (much like when Bill Bryson criticized H. V. Morton!). I used to read everything Pullman wrote, but the Amber Spyglass was such a huge disappointment that I haven’t touched them since. If Pullman didn’t like Lewis’ heavy-handed messaging, then why did he feel the need to use an absolute sledgehammer for his own message, to the point that it severely warped his story? (Though I’m sure he would disagree, ha!)

Anyway, you make very good comments on the Calormen/cultural aspect of HahB, which I was thinking of the other day. I have been reading a book about Genghis Khan and the influence of the Mongols. The author quoted an Arabic writer making an elaborate metaphorical comment: “…the affairs of the world had been diverted from the path of rectitude and the reins of commerce and fair dealing turned aside from the highway of righteousness…” How could that not remind me of Ahoshta’s quoting of poets?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m sorry you were disappointed by The Amber Spyglass, Jean: not originally ever my favourite of the trilogy but one I’ve grown to appreciate much more after a couple of subsequent readings. Since dipping into Pullman’s collected essays Dæmon Voices I’ve discovered that his opinion of Lewis’s Narniad is a lot more nuanced than the one I’ve quoted from a journalist’s article (which appears to go back a few decades). A talk he gave in 2000, ‘The Republic of Heaven’, is more balanced about Lewis, citing Lewis’s essay ‘On Three Ways of Writing for Children’:

“Lewis’s position as a whole wasn’t at all consistent. Whereas the Narnia books illustrate the very antithesis of the Republic of Heaven, his critical writing – as I have pointed out elsewhere – often shows a more generous and sensible spirit. For example, talking about this very business of growing up in his essay, he says, ‘ surely arrested development consists not in refusing to lose old things but in failing to add new things?'” Pullman goes on to say that as an adult he likes hock as well as the lemon-squash, though he wouldn’t have as a child – he’s not lost the old but has gained something new.

Elsewhere he is critical of aspects of Narnia (for instance the put-down of Susan in The Last Battle, a horrible detail I’m sure few of us would disagree with) but nevertheless clearly has great regard for Lewis’s academic work; and of course pays the greatest compliment to what he liked in the Narniad by inventing his own fictional take on it.

I’m sure Lewis was well aware of Arabic writings. According to this web page (http://www.lewisiana.nl/sbjindex/) Lewis’s ‘Surprised by Joy’ alludes to Edward Fitzgerald’s translation of The Rubáiyát of ‘Omar Khayyám, probably a source for Ashosta’s acquaintance with poetry.

LikeLike