The Rime of the Ancient Mariner

by Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

Illustrated by Mervyn Peake,

with an introduction by Marina Warner.

Cover design by Helen Lindon.

Vintage Classics, 2004.

“God save thee, ancient Mariner!

From the fiends, that plague thee thus!—”

Like the Ancient Mariner, whose glittering eye mesmerised the unwilling Wedding Guest, the story and the rhythm and the word choices of Coleridge’s Rime have the power to render the reader spellbound more than two centuries after its composition and publication.

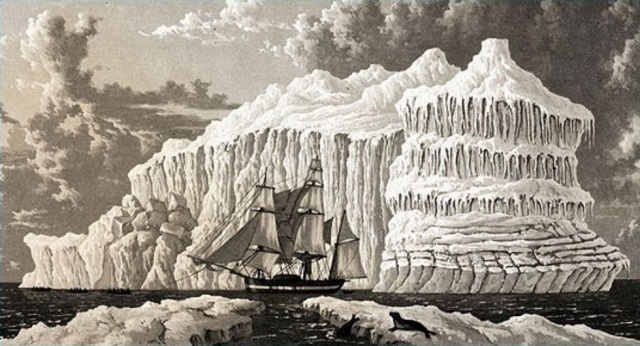

Add to it not Gustave Doré’s engravings – superb as they are – but Mervyn Peake’s haunting images, and then this slim volume of what John Livingstone Lowes described as one of the two “most remarkable poems in English” provides an opportunity to venture into territories which only a poet’s mind can conceive.

And after a perusal – or better still, an incantation – of the poem perhaps we all will, like the Wedding Guest, believe ourselves undoubtedly sadder but also wiser humans.

‘The fair breeze blew, the white foam flew,

The furrow followed free;

We were the first that ever burst

Into that silent sea.’

— Part Two.

Employing a delectably unpretentious literary version of the traditional ballad form Coleridge gives us a narrative of the travails of a seaman who commits an ungrateful act and has to do penance during and after a circumnavigation of the world. Language and imagery are more partners than handmaidens to the story, and the seven-part structure includes a frame that has the mariner forced to recount his misfortunes not just to the wedding guest but to all and sundry.

What is his crime? It’s to have used a crossbow to shoot, for no apparent reason, the albatross that led the sailing ship out of the icy seas of Antarctica. For this the ship’s crew, after a fierce wind has blown them north into the Pacific Ocean, are stuck in the equatorial doldrums where they, one by one, succumb to thirst and die. It’s not until the mariner acknowledges his misdeed and blesses the sea creatures that the curse on him is lifted and, after apparently falling into a trance, he miraculously finds himself back in his home port. But has he expiated his sin? No, for he must now wander the earth and tell all who’ll listen what has transpired.

First appearing in print at the tail-end of the 18th century, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner helped expand the boundaries of literary Romanticism with its occult and supernatural elements: the polar spirits who provided the impetus to the ship’s movement, the figure of Nightmare Life-in-Death who diced with Death for the Mariner’s survival, the entities who took over the corpses of the crew to sail the vessel. But the glory of the poem resides its innate ability to appeal to the imagination, to encourage speculative theories about its meaning, and even to furnish fodder for scholars to research Coleridge’s literary sources and the culture that inspired his vision.

For who can help being moved by the successive horrors that visit the mariner for his thoughtless act – which includes indirectly encouraging his fellow seamen to approve his killing – and the inevitable affects he has on those he then comes into contact with, such as the wedding guest seeing him as a “grey-beard loon”? Who is immune from wondering about the inherent religious symbolism, not just the penance the protagonist has to undergo for his sin but the mentions of crossbow and the albatross hung around his neck like a crucifix, combined with legends such as that of the medieval Wandering Jew?

Marina Warner’s introduction and studies like the classic The Road to Xanadu by John Livingston Lowes (1927) discuss the literary sources that may have inspired the bibliophile Coleridge, ranging from accounts of voyages such as those of James Cook and – famed from the Bounty mutiny – William Bligh, to discussions of magical practices in the Caribbean. Warner doesn’t neglect, however, the likely impact of the author’s drug-taking which it’s known to have influenced the visionary opening of Kubla Khan.

An added reason for acquiring this edition of a work I already had in a couple of poetry anthologies was the inclusion of Mervyn Peake’s artistic responses to the text; eight in all, they range from the “four times fifty living men” who cursed the mariner with their eyes as they “dropped down one by one” to the Nightmare Life-in-Death, an illustration so disturbing it was dropped for the first publication.

But I think the best way to appreciate the sensory experience that Coleridge offers is by reciting the poem to oneself (it takes a little under a half hour) or perhaps even singing the stanzas to one or more traditional ballad tunes. Best choose a suitable melody – in a Dorian or Aeolian mode perhaps – or else the result might be akin to singing Lewis Carroll’s Jabberwocky to the tune of a jaunty nursery rhyme.

It’s Independent Bookshop Week run by Books Are My Bag in the UK and Ireland, so this is a review of a title I purchased at our local indie bookshop, Book•ish in Crickhowell.

It’s only the second 2024 book not from my Mount TBR. The fifth title in my #20BooksOfSummer, it qualifies for the astrolabe, No 8 in Mayri’s Picture Prompt Book Bingo 2024. I’ve now matched ten of the sixteen icons with this year’s reads.

I found reading your review very informative, especially as I have vague memories of having to study this at some point and feeling completely lost. I do wonder if I’d have a better appreciation of it as time has passed since then.

Oh, and well done finding something for the astrolabe on book bingo. That’s the one that I think might defeat my effort to complete the card.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, really the only things that the astrolabe might fit are to do with voyages or sciences such as astrophysics, so I was glad to be able to match it up with this!

I know audiobooks of this are supposed to log in at around 25 minutes, and though I haven’t tried reciting it all in one go I found it really helpful to read a couple of parts aloud to get the feel of the drama and the direction the story was going. Worth a try I think, Lily! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Like Pages and Tea above, I remember this (or part of it) as a school text but not much more other than the albatross and ‘water, water everywhere’. Must revisit it again and try and find a copy with illustrations.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I did it at school too but it lodges in my mind, especially after acquiring and reading a 1978 paperback reissue of The Road to Xanadu (it’s falling apart but I’ve still got it!) which delved into the sources of Coleridge’s visions. This 2004 edition from Vintage Classics (Penguin is the parent company) is still in print if that helps. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I had read something called The Second Person from Porlock a couple of years ago in which one thread was Coleridge and his work, particularly Ancient Mariner and Kublai Khan–including the inspirations behind some of them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I really need to return to my books about the background to ‘The Rime’, ‘Kubla Khan’ and ‘Christabel’ – it’s been decades since I last looked at them properly.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Like Mallika and yourself, I first read this at school, but I’ve read it again several times over the years because I love the imagery, language and atmosphere. Those illustrations look as though they would add something special to the reading experience.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Peake drawings certainly enhanced my reading of it, Helen, and reminded me how mysterious and mesmerising the text is – and even how superfluous the marginal glosses, which Coleridge added in later editions in imitation of annotated bibles, really are!

LikeLike

Large chunks of this seem to be lodged in my brain, ‘He stoppeth one of three..’ The nuns of my childhood were keen on these rhythmic works.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The nuns weren’t all bad then! Did they get you to learn Jabberwocky too? Do try reciting a few stanzas of one and then swap to the other – I find the transitions both natural and yet incongruous, such a weird experience!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Twas brillig and the slithy toves, did gyre and gimble in the wabe.

All mimsy were the borogroves….That’s as far as it goes

LikeLiked by 1 person

Can you guess which is which?

The naked hulk alongside came,

And the twain were casting dice;

‘The game is done! I’ve won! I’ve won!’

Quoth she, and whistles thrice.

One, two! One, two! And through and through

The vorpal blade went snicker-snack!

He left it dead, and with its head

He went galumphing back.

LikeLike

Yep. First four lines Coleridge the second Lewis Carroll (I’d recognise that vorpal blade anywhere) but rhythmically they fit seamlessly.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Don’t they just? I wonder if Carroll was influenced by Coleridge’s ballad.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Love this post Chris – the poem is an old favourite, and I think Peake’s illustrations are some of his finest. Maybe I should go on a Peake binge…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Alongside inside your Calvino and Kafka binges?! 😁

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh god that picture at the top is absolutely terrifying! So glad I didn’t come across it as a child as it’s exactly the sort of thing that used to keep me awake at night.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sorry, maybe I should’ve included a trigger warning! You can see why Peake’s publisher declined to include it for the first edition.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a poem! I remember reading that Thomas Carlyle was singularly unimpressed by Coleridge – ‘His talk, alas, was distinguished, like himself, by irresolution’ – but this does him a disservice. As a sustained feat of imagination and artistry, I think The Rime of the Ancient Mariner is pretty much unique.

Curiously enough, I may have read the version with the Peake illustrations first (we had a copy at home) and I remember seeing some of the originals in an exhibition in Trinity years later. I often wonder if Peake’s work ethic was a factor in his illness; the drawings are very intricate, ergo hard on the eyes, the hands and (most importantly) the brain.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m a little envious that you’ve seen the originals, Aonghus! Were they hand-tinted or merely black and white? Either way – and in this edition they’re not coloured – I prefer them to William Strang’s rather stiff (though competent) series of engravings which Peake must surely have known, along with Doré’s. But the poem itself is almost a force of nature. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

It was a long time ago, but my memory is that they were pen and ink and were around A3. As always, you’re much more conscious of the effort on the artist’s part when you’re viewing his work firsthand (or at least, that’s how it affects me). Also of a very distinct personality at work. Van Gogh’s stuff made the same impression on me. Also – surprisingly – Monet. I always thought his stuff looked a bit like it should be on a chocolate box until I saw it firsthand. He really is very good.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Seeing an artist’s work firsthand is always desirable, though I’m always grateful that so much art is available to view online or in publications.

LikeLike

What Laura said about the first image, esp as it revealed itself slowly as I scrolled down. I, too, “did” The Ancient Mariner, but I think at university rather than school. I mentioned him to my husband the other day (why?) and he’d never heard of him!

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Peake version of Life-in-Death is singularly striking isn’t it! Yet it’s extraordinary how the Rime goes from school syllabus (I ‘did’ it at school in the 60s) to set university text (umpteen courses on the Romantic poets) and then gradually drops out of general consciousness. You’d think, with its characteristic weird vibes it’d be as adapted as Frankenstein or Dracula!

LikeLiked by 1 person