Moonstone: the boy who never was

by Sjón (Sigurjón B Sigurðsson).

Mánasteinn: Drengurinn sem aldrei var til (2013)

translated from the Icelandic by Victoria Cribb.

Sceptre 2016.

Reykjavik has, for the first time, assumed a form that reflects his inner life: a fact he would not confide to anyone.

Chapter XIX

This wonderful heartfelt novella leaves a lasting impression of a couple of months in the Icelandic capital as winter approached at the end of 1918. Through the life of Máni Steinn Karlsson — the boy who never was — we the readers experience a tumultuous epoch in history, affecting millions around the world but in such different ways; and Sjón’s writing, using short chapters and the historic present tense, has an immediacy and vividness that both appalls and attracts as it draws us in: it’s not for the squeamish.

Although written in 2013, Moonstone remains strangely relevant in 2022. My reading of it in the middle of a global pandemic also coincides with the eruption of the Hunga Tonga–Hunga Haʻapai volcano on the Pacific Ring of Fire, both of which events echo the arrival of influenza in Iceland, scant days after the explosive eruption of Katla, which forms the background of the novella.

This is stark writing capturing the bleakness of life a century ago, a monochrome diorama shot through with flashes of colour, especially red. But instead of creating distance, as can be the case with some historical fiction, the author includes a kind of epilogue which makes it clear that this story is of personal significance and importance: in an interview he emphasises that it contains “the untold stories of my gay friends and the shadowy existence they were forced to live until recently.”

Máni Steinn is an outsider, an outcast, his existence conditioned by plagues of different kinds. An orphan, born in 1902 in a leper hospital outside town, later suffering in the 1918 influenza epidemic, his homosexuality will link him to later generations who succumbed to the so-called ‘gay plague’ of the HIV-AIDS years. Though — or perhaps because — he is largely illiterate, he is drawn to the black-and-white silent films shown in the town’s two cinemas, and becomes especially fascinated by fantastic movies such as Louis Feuillade’s Les Vampires.

This fascination is imprinted on the person of Sóla, a blackclad motorcyclist who rides a crimson Indian bike and wears a red scarf which she then gives to him. Meanwhile Máni himself gives rides to his ‘gentlemen’, as we’re told in graphic and explicit descriptions. Sóla and Máni of course are the names for the siblings who steer the chariots of the sun and the moon in Icelandic myth, by which Sjón means us to understand that this tale of ‘the boy who never was’ is as much symbolic as realistic.

As the Great War neared its end, the coincidence of Katla’s eruption in October and the arrival of the flu virus on a Danish ship — its contagion promoted by the popularity of the picture houses — followed soon after by Iceland’s assumption of sovereign status on the first day of December, forms the background on which the story of Máni is projected like a movie. Sjón knows that illusions, whether on a cinema screen or in one’s inner life, inevitably reflects and is reflected by real life, and that sometimes the two states seem to merge.

For me, Moonstone is at once a tale of compassion, a plea for acceptance and a lesson in understanding, qualities which now as ever are urgently needed. I’m glad to have read it.

It is amazing to imagine that a short novella could contain all of those powerful themes.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes, 147 pages of fairly large type, often with blank pages to separate the short chapters — a lot to pack in, but except for the last page or so of context all told in such matter-of-fact language (Victoria Cribb’s translation never stumbles) that readers are able to draw out all the themes for themselves, should they choose to. I’m glad I got past the first graphically explicit first chapter!

LikeLike

I’ve only one Sjon book, The Blue Fox, which was rather wonderful too combining the mythic with history in the rural past. Another novella, it was also full of powerful imagery. I’d certainly like to read this one of his, and your timing of reading it certainly resonates.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I really liked Sjón’s literary style and sensitivity here so I’ll definitely be looking forore of his writing, including I’m sure The Blue Fox.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another new-to-me author, though considering I’ve read very little Nordic fiction so far, that isn’t surprising. This does deal with so many relevant issues even for the present. Must make note of this

LikeLiked by 1 person

Be warned, there are very graphic sex scenes from the start, but in the context of what Sjón says he’s trying to do — to honour his gay friends who will have been persecuted unless they lived “a shadowy existence” — they’re probably essential to give a full picture for our better understanding.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That might be a bit off putting since I am not a fan of too much explicit content in general.

LikeLike

Nor me, Mallika, and I was strongly tempted to put it aside; however, because it was historical fiction — focused strongly on 1918 — I decided to plough on, making the whole effort worthwhile.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The time period/setting appeals to me too

LikeLiked by 1 person

The author’s The Blue Fox (the fable mentioned by Annabel) gets some positive reviews on Goodreads, and that may be a better place to start. It’s also translated by Victoria Cribb whose rendering of Moonstone felt seamless to me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

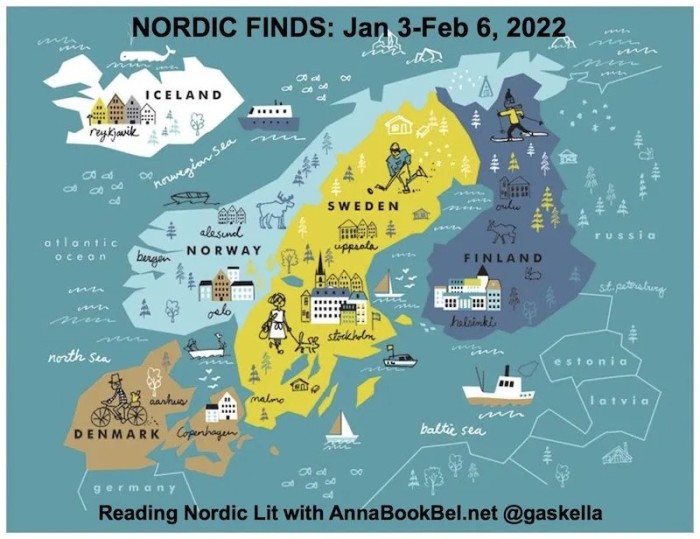

Pingback: #NordicFINDS is here! (Sticky) – Annabookbel

There’s always something rather fascinating about Iceland … I’ve read several of Arnaldur Indriðason’s crime novels, and I loved the first series of Trapped (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trapped_(Icelandic_TV_series)) …

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have a couple of other Icelandic novels to read at some stage and the odd saga to reread, but not just now, though I will check out Indriðason. I see that BBC Four first showed ‘Trapped’ a few years ago, so it may be possible that it’s still available on iPlayer — though probably not.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve just checked and, alas, Trapped is NOT available on iPlayer at the moment …

LikeLiked by 1 person

Probably just as well, too much else queued up to watch. And there are the books… 😁

LikeLiked by 1 person