The World According to Anna

by Jostein Gaarder.

Anna. En fabel om klodens klima og miljø, 2013,

translated from the Norwegian by Don Bartlett.

Weidenfeld & Nicolson 2015.

When the original subtitle of a novel reads “a fable about the earth’s climate and environment” then you know there’s a lesson being offered. Though fables are usually defined as short stories with a human moral featuring animal characters, Jostein Gaarder’s tale is longer than most such fables, and its moral features the animals as victims of humanity’s dubious morality.

With any literary fable there is a worry that increased length may affect effective storytelling, with the moral risking being the tail that wags the dog. Gaarder doesn’t always successfully maintain the balance, I feel, but he does it with style and evident passion and furnished this reader at least with much to think about.

Anna is due to turn sixteen at twelve midnight on the twelfth day of the twelfth month in the twelfth year of the 21st century. But she keeps having vivid dreams about a girl called Nova seventy years in the future. And what a future: in 2082 the world’s climate has already got out of control, meaning mass extinctions, human migration from lands rendered uninhabitable, and a massive reduction in the world’s population. On the plus side everyone can access virtual images of what the world was like, and view holograms of creatures once on a red list while having to pollinate fruit trees by hand — because there are no bees.

The narrative swaps between Anna’s story (told in the past tense) and Nova’s (mostly in a continuous present), a technique designed to further disconcert the reader: are we in the future looking back or in the past imagining the future? Because that future is unutterably bleak unless — somehow — we humans are given a second chance to right the wrongs we are collectively doing to ourselves, to nature and to the planet. But even with a second chance would we do what, morally, we should?

Gaarder’s novel paints a diptych of Nova’s life with her parents and her 86-year-old great-grandmother (whom she calls Nana) side by side with Anna’s in 2012. Anna’s intensely real dreams, with her living Nova’s future life, at first result in her visiting a psychiatrist; meanwhile — narratively speaking — Nova starts to have some inkling of her Nana’s identity as Nova too senses a virtual connection with Anna seventy years before. Both girls are developing a close bond with a significant other who share their concerns for the planet; and both are somehow linked through the ownership of a ruby ring of great antiquity.

Like much of Gaarder’s writings which I’ve read, the story gives us lots of incidental details which it is up to us to fathom whether they’re significant or not. For example the colour red runs like a scarlet thread through both the girls’ lives, from the ruby ring which may or not be the magical object in the tale of Aladdin through balloons and dresses and walls and much else. Are we to bring to mind red lists of endangered species, or a heated planet, or a womb-like environment? Who’s to say whether we’re meant to accept any or all of these allusions?

Anna’s experiences for the reader are more relatable than Nova’s, for obvious reasons, but both are determined to be activists. Anna’s decisions and actions may remind us a bit of Greta Thunberg’s, but we should recall that the Swedish girl began her school strike as recently as September 2018, five years after this novel appeared. But in those five years much had got worse, with Thunberg’s clarion call (“Our house is on fire”) in January 2019 ever more urgent than before.

In many ways this fable is a bit of a mess: too long, too diffuse, well-meaning but very probably preaching to the converted. But its central moral — that generations living now are responsible for the world they bequeath to future generations — cannot be denied. If at the very least it gets us to think and at best spurs us to get active, then it has served what seems to be its principal purpose.

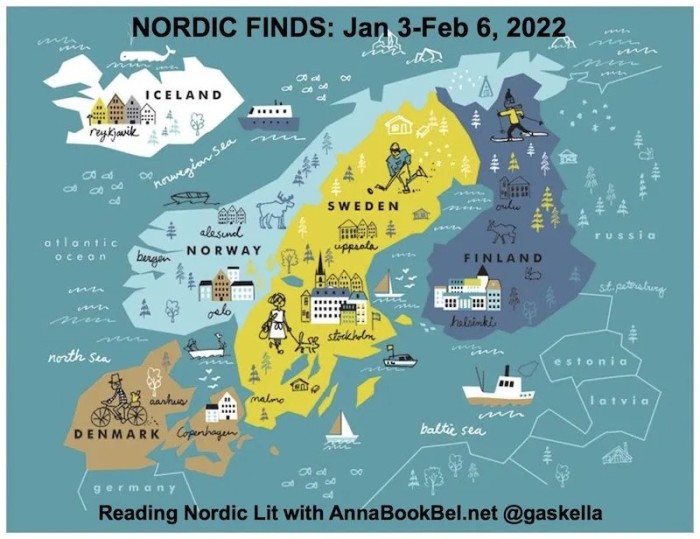

I think I may have enjoyed this one better than my re-read of Sophie’s World, which I got rather bogged down in. Thank you so much for taking part in #NordicFINDS

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome, Annabel — as I say, I have another two or three Nordic titles lined up for later this month! As for Sophie’s World, I too read it way back, along with The Christmas Mystery, and the latter almost put me off reading anything by Gaarder again! However, I enjoyed The Ringmaster’s Daughter and The Solitaire Mystery rather more, so I haven’t totally given up on him.

LikeLike

Pingback: #NordicFINDS is here! – Annabookbel

The only Gaarder I’ve read was Sophie’s World, and frankly that was so long ago I can remember little, although I think I was a bit out of my depth with it. I’d probably get on better with him nowadays but I admit i’m not desperately drawn to explore further!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You might enjoy Gaarder’s magic realist novel The Ringmaster’s Daughter

(reviewed at https://wp.me/s2oNj1-spider) which I found more effective than his The Solitaire Mystery, though that still intrigued me (https://wp.me/p2oNj1-65). But life’s too short to read stuff you’re not drawn to, Karen, so I wouldn’t feel pressured if I was you — and certainly not where this latest Gaarder offering is concerned!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I never thought of looking up Gaarder’s other books but this is giving me similar vibes to Sophie’s World in terms of how we see or interpret the two storylines.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Gaarder does seem to have a distinct style of his own, Mallika, which one either appreciates or doesn’t. I’m not a hurry to read him in the near future, but I admit rather shamefacedly that I have had a copy of his novel Maya on my shelves for quite a while.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve only read Sophie so far, and I did enjoy the way he put across the crux of Western philosophy in a fairly simple way. The twist in the story itself was one I didn’t see coming and I wasn’t quite sure how to interpret it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I may have to reread SW sometime as I read it within a year or two after it first came out in the early 1990s and I only retain faint impressions of it.

LikeLike

I read a few of Gaarder’s books in the 1990s and remember enjoying Sophie’s World and The Solitaire Mystery. I keep meaning to go back and investigate the ones I missed or that have been published since then, but have never got round to it. This one sounds interesting and relevant, but I’m not sure that it really appeals to me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’d skip it and try The Ringmaster’s Daughter, Helen, so much more satisfying as fiction than this, however laudable and well-intentioned it is: Gaarder’s own concerns about the climate crisis — valid concerns, I agree — come across really strongly, but as a story it doesn’t quite hit the mark for me.

LikeLike

I have enjoyed several books by this author, but I think I’ll stay away from this one, “too long, too diffuse”

LikeLiked by 1 person

As with Helen in my reply above I’d say go for one of his others before considering this one, Emma — but I need to try a few more of his titles to feel confident about where this ranks in Gaarder’s output!

LikeLike