“Behold there was a very stately palace before him, the name of which was Beautiful; and it stood just by the highway side.”

— John Bunyan, The Pilgrim’s Progress

Reading Susanna Clarke‘s novel Piranesi awoke all kinds of echoes for me. The repetition, especially, of the narrator’s paean of praise to the place in which he resided — The Beauty of the House is immeasurable; its Kindness infinite — reminded me of texts such as John Bunyan‘s Pilgrim’s Progress and the refuge to which Christian sought entry, the Palace Beautiful, the way to it guarded by a pair of chained lions (not unrelated to Aslan, I suspect).

But there were other literary reverberations which were set up in my mind, stretching from classical Greece and Rome to this century; in the event that you may find of interest I’ve put together the following illustrated essay.

Be warned, though: in discussing the ideas behind various works of fiction I shall be giving away the odd secret or spoiler so, if you haven’t read them, you may want to skim over or even skip the text and just enjoy the illustrations.

In the Middle Ages and the Renaissance a mental exercise which the Roman orator Cicero described was never entirely forgotten: he reported how the Greek poet Simonides was able to identify bodies crushed by a collapsed building by remembering where individuals had been sitting at a banquet before the hall fell in. From this Cicero deduced that

“persons desiring to train this faculty [of memory] must select places and form mental images of the things they wish to remember and store the images in the places, so that the order of the places will preserve the order of the things…”

Thus with a vivid image of a real structure — a building or façade, for example — one might employ both place and images “as a wax writing-tablet and the letters written on it.” As an orator Cicero found this a useful rhetorical aid, as Frances Yates describes at the start of The Art of Memory; and — whether in the form of the plan or elevation of a piece of classical architecture or (in the Middle Ages and later) of a theatre — the doors, windows, niches and pillars of buildings were to prove crucial in the development and persistence of ars memoriae.

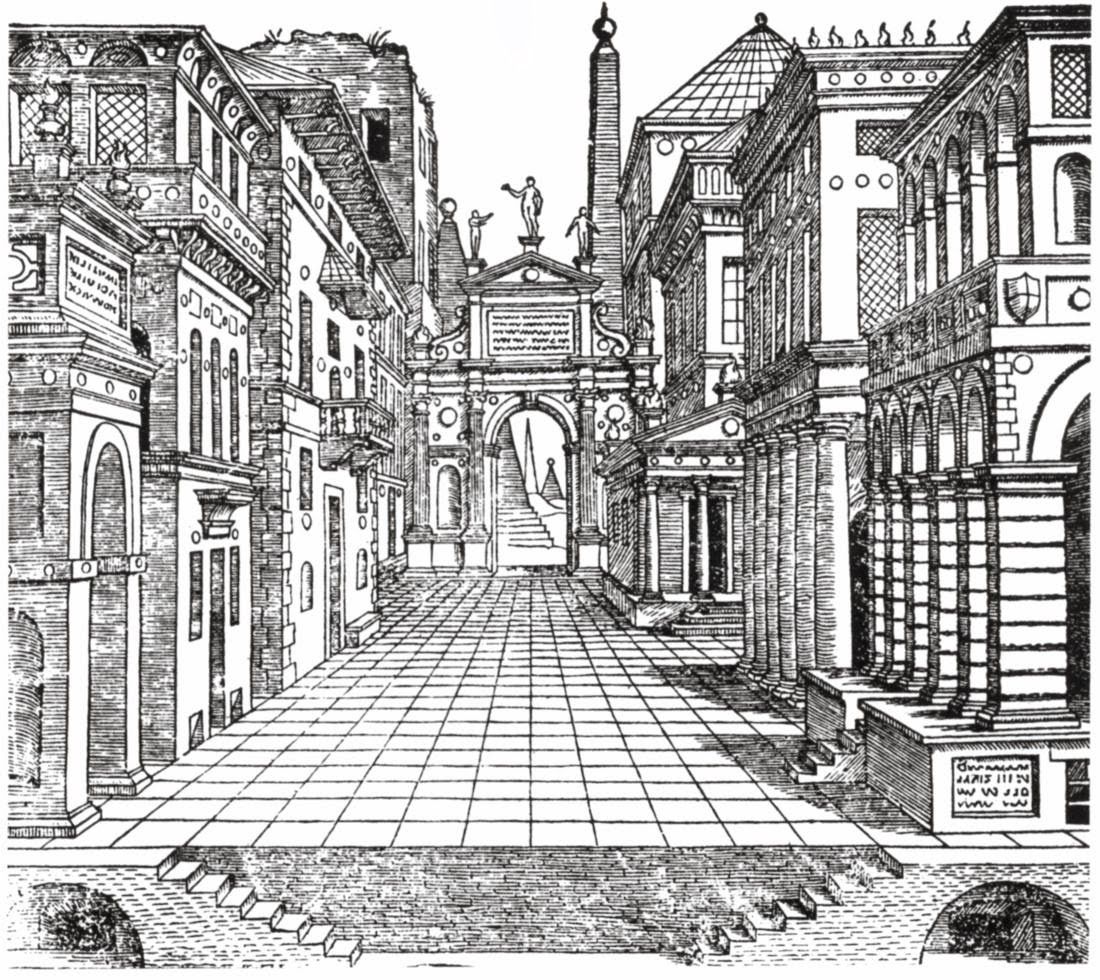

The concept of a façade or enclosed space being like a wax tablet which one could read transferred readily to the printed page, especially in the illustrations and diagrams which were disseminated widely after printing presses proliferated in the Renaissance. Writers who promulgated the technique through books included Giulio Camillo, Giordano Bruno and Robert Fludd.

But architectural drawings didn’t just serve the mnemonic skills, they also tickled the fancy of lovers of the fantastical. In the 18th century Giambattista Piranesi (1720–1778) made a name for himself as a painter and architectural engraver, depicting buildings both real (either ruined or restored) and imaginary (projected or fantastical). In particular his Carceri d’invenzione, or ‘imaginary prisons’, consisted of sixteen prints in the second (1761) edition of underground vaults, piers, staircases, Cyclopean statues and Lilliputian figures.

The enclosed spaces of Piranesi’s imaginary prisons will doubtless have influenced Susanna Clarke’s concept of the House in Piranesi, along with the other fantasies he did of urban townscapes in ancient Egypt, say, or Rome. To these Clarke has added Jungian touches, such as the flooded lower levels of the House and its upper levels through which clouds float, and the presence of fish and birds.

Another writer whose fantasies included antique buildings was Edith Nesbit, for example in the third of her Psammead novels called The Story of the Amulet. Here the siblings of Five Children and It get to travel in time and space to Mesopotamian palaces and the mythical city of Atlantis. They in fact witness the start of the destruction of the lost continent with the first of the great tidal waves thundering onto the city below the palace, a distressing experience for them but one may have contributed to Clarke’s House.

C S Lewis acknowledged the influence of Nesbit’s children’s fiction in his Chronicles of Narnia right at the start of The Magician’s Nephew. I see aspects of her palace of Babylon and city of Atlantis — the monumental statues and the gargantuan architecture — repeated in the uninhabited palace and city of Charn, just as I detect in Charn’s ruinous state the evident dilapidation that’s affecting the House.

Imaginary cities and buildings are of course a staple of speculative fiction, most notably in Tolkien’s works: one has only to think of Minas Tirith, say, Isengard or Cirith Ungol. A variation on this occurs in Ursula Le Guin‘s early SF novel Rocannon’s World when the eponymous protagonist finds himself and some companions trapped in a strangely symmetrical but labyrinthine structure inhabited by silent winged beings; we almost imagine them as angelic until Rocannon realises they are an insectoid species and that he is likely to be live food for grubs in a giant hive.

Returning now to fantasy, we know that Philip Pullman‘s trilogy His Dark Material in part references Lewis’s Narnia stories. In particular Pullman’s Cittàgazze emptied of adults in The Subtle Knife (1997) recalls Charn, and the Republic of Heaven, the Land of the Dead and the world of the mulefa echo aspects of Narnia itself. You should also know that Pullman’s Cittàgazze is reputedly inspired also by Brian Aldiss‘s The Malacia Tapestry (1976) which features an Italianate city and is illustrated by engravings by the 18th-century Venetian artist Giovanni Battista Tiepolo. Aldiss is variously claimed to have based his Malacia on either Venice or Ragusa (modern Dubrovnik), or possibly both.

The Chronicles of Narnia also directly inspired Lev Grossman‘s Magician’s trilogy, and in the second volume, The Magician King (2011), we hear more about the Neitherlands [sic]: this uninhabited neoclassical city is a cross between Lewis’s The Wood Between the Worlds (with fountains functioning as portals to worlds) and the crumbling city of Charn.

There are various strands which it’s possible to follow through in this discussion of fictional cities. First, the urban landscape is often of a neoclassical or Mediterranean nature; in some cases there is abandonment and/or decay evident. Then we note the motif of memory, either with the Palladian edifices being used to enhance recall or, in the case of Susanna Clarke’s fiction, leading to selective amnesia. Finally we detect elements of occultism and magic, with the cities either providing portals to other worlds or being inhabited by beings with natures often very different from their human visitors, even if some of these are accomplished magicians.

Our starting point was a novel by Susanna Clarke, and we end with another, namely Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell. There are numerous urban environments here (and a few non-urban too) including York, London and Venice, with some providing portals to and from Faërie for one particularly sinister individual. Yet none quite match up to the majesty, vastness and mystery of Piranesi’s House.

Main titles mentioned (links in the discussion are to my reviews)

- Brian Aldiss, The Malacia Tapestry. Triad Granada 1984

- Susanna Clarke, Piranesi. Bloomsbury 2020

- Lev Grossman, The Magician King. Heinemann 2011

- Ursula K Le Guin, ‘Rocannon’s World’ in Worlds of Exile and Illusion. Orb 1996

- C S Lewis, The Magician’s Nephew. Armada Lion 1980

- E Nesbit, The Story of the Amulet. Puffin Classics 1996

- Philip Pullman, The Subtle Knife. Scholastic 2000

- Frances A Yates, The Art of Memory. Peregrine Books 1969

Nice post! I’ve finished it a few days ago, didn’t have time for a review yet.

You think the sea/clouds are Jungian? Could you elaborate a bit? I’m not well versed in the man’s ideas.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Bart, and now I’m eagerly anticipating your review! I have more to say about Piranesi but I’m spinning out the time while I continue digesting its impact on me.

I seem to remember Jung describing patient dreams (and his own too) as based around a house or other dwelling, with deep significance attached to going down to a cellar, say, or up to the attics, and what might be waiting there or, indeed, discovered. I shall have to look it up. And of course, Norse myths have this thing about a world tree, its roots and branches, and the main post of a hall (like Barnstokkr) being its symbol.

I think the House in this novel is intended to psychologically represent Piranesi’s concept of his world—doesn’t he allude to that in the text? So seas below, the heavens above, all very, er, Jungian.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Some fascinating connections here, and if I may I’d like to add the Palace of Diocletian in Split as another urban labyrinth: trails round corners, and back in time, steps retraced and the modern world impinging…

The oddest thing were the two lads at one of the entrances in Roman soldier “uniform” for the tourists: seen once or twice on duty, they were at their best when on their lunch break, sitting in the shade eating bread and cheese, just like the people they were representing may have done: a “time no more” moment, to add another book to the discussion…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Cheers, Nick: when I read Aldiss’s The Malacia Tapestry I envisioned Split in my mind as much as I did Venice, and drew up a map which I’m sure was partly influenced by Diocletian’s Palace (though I’ve never been, only researched in atlases and text books—no Internet then!).

The soldiers, yes, I can imagine that: whether outside the Pantheon or by the Colosseum I’ve seen their colleagues lounging around just as their historic counterparts may have done off duty!

LikeLike

A fabulous post and wonderfully illustrated, I’ll need to come back for another look!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m so glad, thanks, Jane—I certainly enjoyed putting it together.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wonderful stuff. Piranesi’s drawings were amazing, and you remind me how brilliant Pauline Baynes was too.

LikeLiked by 2 people

At some stage I’ll do a post not of Piranesi’s prisons but his fantasy architecture, and discuss how I think he achieves his sense of grandeur. And Pauline Baynes, she did have a wonderful style which seemed infinitely adaptable to its subject matter.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I see you enjoyed Piranesi quite a bit, it seems to have inspired you, Chris, to go in many intriguing directions! A highly interesting post, it actually makes me curious about Clarke’s novel for the first time! 😀

LikeLiked by 2 people

All I can say, Ola, is — Read it! Beg, borrow, steal it and you won’t regret it!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Just finished Clarke’s latest myself, and I agree with you, Chris, that it’s a must-read. The MC’s mostly solitary life certainly fits in with what many have experienced over the past year.

To your list I would add Lawrence Durrell’s The Dark Labyrinth, and perhaps Gaiman’s Neverwhere. Having finished Clarke, I’m spurred to reread those two.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think the scenario reflects Clarke’s own isolation suffering from a form of CFS, but its publication at the present time gives it a more universal relevance, I agree.

Emily read Durrell’s Alexandria Quartet years ago, but I’ve never tried him — though since you rate The Dark Labyrinth I’m now intrigued! I read Neverwhere years ago and wonder if it’s time for a reread for me too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Dark Labyrinth is nothing like the Alex Quartet, and thus not quite as good. But still a great yarn.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Probably nothing like, but looking at the blurb this reminds me of Patricia Highsmith’s Two Faces of January, in part also set on Crete: https://wp.me/s2oNj1-january

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is an entire post on fictional and mysterious / labyrinthine / portal cities. I just loved looking at the imagery and connecting it with different strands from Piranesi. The most curious thing about reviews of Piranesi is that the reviews just keep adding to the mystery that is the House. It’s a compound effect. 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

I would like to reread Piranesi sooner rather than later, I think, and possibly pick up on details I may have missed before. But because it takes on the nature of a dream I’m not sure I’d really be any the wiser! Still, I enjoyed your review very much, thanks, having picked up on it from imyril’s Quest Log the Third.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: So long, hiatus | Lizzie Ross