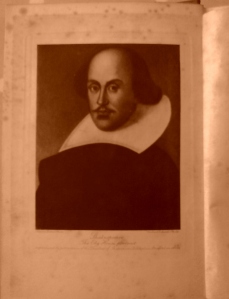

William Shakespeare

The Tragedie of Cymbeline

Act I in six scenes

The Medieval and Renaissance sense of the past was particularly liable to admit anachronisms, for example narrating how pre-Christian classical heroes would go to Mass before setting out on their adventures. In Cymbeline Shakespeare had no worries about anachronistic details: a story set just before the arrivals of the Romans in Britain includes for example men from France, Holland and Spain, when these countries were yet to come into existence, and its curious mix of Welsh, Italian and Latin-sounding names is quite disconcerting. But the author cares not a jot or a tittle about this, for this is principally a fantasy about power struggles in high politics, conducted by individuals with very human failings. Like many a Shakespearean comedy (don’t be fooled by the ‘tragedie’ label of its original title) it is essentially a fairytale full of all the folktale motifs and themes that we expect from traditional stories.

The first scene, set in Cymbeline’s palace, is essentially a long involved backstory as told to one gentleman by another — actors who undertake this scene have their job cut out to make it not seem tedious. The two young sons of Cymbeline, king of Britain, had been kidnapped at an early age, leaving the king to lavish his hopes on Imogen his daughter, whose mother died giving birth to her. With Cymbeline remarrying a widow (whom, curiously, we only ever know as “the Queen”) the expectation is that Imogen will marry Cloten, the Queen’s son by her former marriage. However, Imogen has upset the applecart by marrying an impecunious orphan, Posthumus Leonatus.

When the Queen appears it is to assure Imogen that she is not the wicked stepmother of legend, referring to the “slander of most stepmothers” who may appear “evil-eyed unto you”. From which we must think the lady doth protest too much, especially as her perfidy becomes almost instantly obvious. When Cymbeline himself appears it is to again express his anger at the unauthorised marriage and to confirm both the banishment of Posthumus and the house arrest of his own daughter. There are shades here of Lear, like Cymbeline another figure from Geoffrey of Monmouth’s pseudohistory The History of the Kings of Britain.

The second scene introduces us to the dolt that is Cloten, the Queen’s son, followed by a scene between Imogen and Posthumus’ servant Pisanio in which her fidelity to her husband is reinforced. The scene then shifts to Rome, to which Posthumus has travelled. Here he commits the mistake of bragging of his wife’s beauty and fidelity; this is followed by a further sin of accepting a wager that the wily Iachimo can tempt Imogen into being unfaithful, a misjudgement compounded when he gives up as surety the ring that is the token of their loyalty. You can be sure that Iachimo, virtual namesake of Iago in Othello, will be using the ring to further his ruses.

In the fifth scene we return to Cymbeline’s palace where we encounter the Queen in best Lucrezia Borgia mode as poisoner. She palms some poison off on Pisanio as a concoction that will restore the dead to life, not knowing that her physic teacher, Cornelius, had instead supplied a draft that would only “stupefy and dull the sense awhile,” giving the semblance only of death. We can suspect where this thread is going. Just before the end of Act I Iachimo makes his way from Rome to Britain where he supposedly ‘tests’ Imogen’s fidelity — both with weasel words of a gold-digging Posthumus once abroad forgetting Imogen and also by a clumsy kiss — only to immediately set a trap by asking her to safeguard a trunk full of plate and jewels destined “for the emperor”. We can guess what surprise this treasure chest contains.

So, by the end of this first act we are presented with two obvious villains — the Queen and Iachimo — and a pair of married lovers whose loyalties are to be tested to their limits. Are we to regard the box of poisons and the treasure chest as McGuffins, or will they play the parts that Shakespearean comedies and fairytales demand? Why is the play called Cymbeline when so far all he has done is to appear as the irascible father of the bride? And when and where do the two missing princes come in, as they must inevitably do?

It’s too soon for me to say how this measures up to his other plays of this time, Shakespeare’s so-called ‘late period’. The Winter’s Tale and The Tempest appear to have bookended Cymbeline in terms of chronological composition, and all three were first performed during 1611, five years before Shakespeare’s death. The two other plays, while better known, appear to share several themes, most obviously that of the ‘lost’ royal child or children (Perdita’s name even means “lost”, while Miranda “the wondrous one” was lost, set adrift at sea at the age of three). The corresponding infants in Cymbeline are called Guiderius and Arviragus; needless to say this theme is unhistorical, Cunobelinus having no offspring with these names (though a contemporary figure was indeed called Arviragus).

So far I’ve not encountered any familiar quotations indicative of a highly-regarded familiar text. It may be that the density of metaphors make many passages tough going, though Iachimo’s oily wooing of Imogen is particularly thick with conflicting images, as in this passage:

… Should I, damn’d then,

Slaver with lips as common as the stairs

That mount the Capitol; join gripes with hands

Made hard with hourly falsehood—falsehood, as

With labour; then by-peeping in an eye

Base and unlustrous as the smoky light

That’s fed with stinking tallow; it were fit

That all the plagues of hell should at one time

Encounter such revolt.

Early days, then, and no immediate rush to judgement.

The trunk, with its dubious contents, and the non-poisonous poisons: Feydeau must have loved these. But why didn’t Iachimo use that ring in his efforts to bed Imogen? What’s he saving it for?

It’s clear also that Imogen sees through the Queen’s protests: “O/Dissembling courtesy!” says Imogen to Posthumus. “How fine this tyrant/Can tickle where she wounds!”

LikeLike

It’s promising as a set-up, isn’t it? Lots of elements that you can’t quite predict how they’ll interact before the denouement, and Iachimo and the Queen both as devious as can be.

LikeLike

My sister died suddenly when she was seventeen. It was the first time I think I’d experienced the grief of death so close and found it hard to cope with. It was a few weeks later, while watching a BBC Shakespeare Cymbeline that the tears finally flowed. “Fear no more the heat of the sun.” Always liked Cymbeline since then.

LikeLike

Grief like that must be hard to bear, Simon, so I’m relieved that this play might have had a healing effect for you. Do hope that in reviewing it we tread softly on your emotions.

LikeLike

Pingback: Cymbeline II: The Trunk | Lizzie Ross