Diana Wynne Jones Wilkins’ Tooth

Collins Voyager 2002 (1973)

Published 1974 as Witch’s Business in the USA

Is it possible for there to be too many ideas in a novel? Especially in a children’s story of barely two hundred pages? In Diana Wynne Jones’ very first children’s novel images and themes and borrowings and emotions all come out fizzing and popping, like fireworks that one can gasp at while scarcely having time to reflect before the next effect bursts into view.

The book is dedicated to one Jessica Frances, and what better compliment can an author pay to a dedicatee than including them, however obliquely, in the story. Jess and Frank are twins who, bitter at being stopped their pocket money, set up what they hope is a money-making scheme that will simultaneously feed their need for cash while getting a sort of revenge for their economic disempowerment. Jones has written about youngsters’ constant cries of “It isn’t fair!” as not being an adequate response to their situation (Reflections 52-3). A better response, she says, is humour and by the end of the book humour is what wins the day rather than pure revenge, because, as Juvenal in his Satires said, “Revenge is sweet, sweeter than life itself — so say fools.”

Jess and Frank put up their sign on the shed at the bottom of their garden:

OWN BACK LTD

REVENGE ARRANGED

PRICE ACCORDING TO TASK

ALL DIFFICULT TASKS UNDERTAKEN

TREASURE HUNTED ETC.

Soon they are inundated with requests by individuals wanting to ‘get their own back’, that is, revenge for real or perceived slights. Unfortunately, the twins’ attempts to make money backfire as they get paid back with increasing complications and problems. Neighbourhood bully Buster Knell wants one of Vernon Wilkins’ teeth because Vernon has stood up to bullying and knocked out one of Buster’s teeth. Two sisters, Jenny and Frankie Adams, want revenge on a dotty old lady for giving Jenny the Evil Eye and making her lame. Martin Taylor wants the twins to stop the two sisters from harassing him. Each job has unforeseen knock-on effects, turning ordinary events into nightmare situations. And the dotty old lady, Biddy Iremonger, is more than she seems.

Diana Wynne Jones’ debut novel for young people appears to spring miraculously out of nowhere like Athena from Zeus’ head, setting both the tone and the standard for what came later. And its not just for young people either — adults with their broader life experiences can appreciate the nuances as much as the narrative and be startled by the cultural references as much as they’re dragged along by the plot. Let’s start with names. We’ve already been alerted by the dedication; now to turn our attention to the title.

I remember from my schoolboy history a notorious British imperial adventure called the War of Jenkins’ Ear. In this ten-year naval war against Spain the initiating incident involved Robert Jenkins who, sailing from the West Indies, was stopped by a Spanish ship and then had his ear summarily sliced off. The British retaliation, which was only commenced some years later, was given its fatuous title a century later to underline the ridiculous nature of a minor fracas escalating into a major conflict; Jones did well to resist calling her story The War of Wilkins’ Tooth in emulation of this episode, bearing in mind the narrative parallels. Why tooth, though? She as good as cites the Old Testament injunction of ‘an eye for eye, a tooth for a tooth’, an amoral justification of vendetta which is endlessly played out around the world, to the shame of peoples and nations.

Pride of place for choice of names goes to Biddy Iremonger. ‘Biddy’ is of course a common name given to old ladies of an inconsequential nature, a familiar form of Bridget, but this biddy is not inconsequential at all. Iremonger reminds one first of all of ‘ironmonger’, but here it also suggests someone who deals in anger, a contradiction of that ‘biddy’ label. At one stage her name is misspelled as B Ayamunga, and I’m sure I’m not the first to see leap out the name of that infamous Slavic folklore witch Baba Yaga. Jones would have been very familiar with this bogey figure, not least from Old Peter’s Russian Tales, a book by Arthur Ransome which her father grudgingly provided when she and her sisters were young. Ransome (whom Jones actually saw when she was evacuated during the war to the Lake District) retold a Russian folktale as “Baba Yaga and the Little Girl with the Kind Heart”, describing the witch as having iron teeth as well as the cannibalistic tendencies of the Hansel and Gretel witch; she lived in a little hut which stood on hen’s legs and flew around in a mortar with her pestle and besom broom.

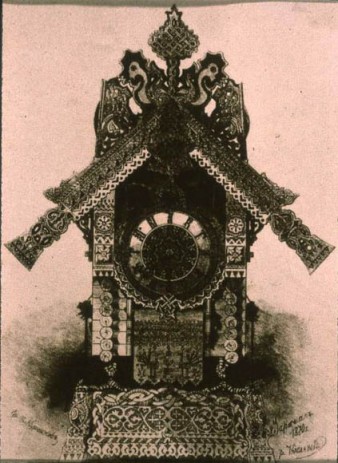

The hut on fowl’s legs famously features as one of Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, inspired by a real exhibition which included Victor Hartmann’s design for a cuckoo clock based on Baba Yaga’s hut. Like her Russian counterpart Biddy has a hut with a cockerel on the roof (though the structure doesn’t move) and a cat that prowls around; though she lacks the iron teeth the name Iremonger is suggestive. And — the clincher here — she not only is a witch with terrifying and almost limitless powers but also proves capable of enormous cruelty to children. Powerful. Vindictive. Cruel. How can she ever be defeated, and by mere kids?

The answer seems to be to use humour and a sense of playfulness. Laughing at an opponent is a rather dangerous strategy but generally laughter can help raise the spirits, while a sense of playfulness can lead to solutions. Jess’ remembrance of a favourite fairytale, Puss in Boots, allows her to work out how to defeat Biddy. As the author herself points out (Reflections 126) Jones doesn’t consciously use folktale motifs, rather they ‘present themselves’ and the ‘weight they carry is only to be grasped intuitively’, so Jones’ intuitive usage of the motif only represents poetic justice. In almost the same breath she references Wagner’s Rheingold, specifically the point at which Alberich is tricked into shape-shifting into a toad’s form, a hint at her multiple influences.

The mention of the treasure and waters of the Rhine draws in more strands that manifest themselves in Wilkins’ Tooth. The river that runs past Biddy’s hut (echoing the tears that run down the faces of a couple of characters) is not just a reminder of Baba Yaga’s difficulties in crossing water but a nod towards the treasure of the Rhine Maidens, the Rheingold of Wagner’s music drama and German myth. Another strand running through this novel is the search for missing heirlooms in the form of treasure, a common enough motif to be sure. Here I am forcibly reminded of E Nesbit’s The Treasure Seekers — this being, as the subtitle proclaims, the Adventures of the Bastable Children in Search of A Fortune. Jones’ son Colin Burrows tells us that Nesbit was “the biggest literary influence on his mother” and “the main spirit behind Diana Wynne Jones’ fiction”. I can’t help thinking that Jess and Frank’s selfish efforts to raise cash becoming the selfless quest for Jenny and Frankie’s family heirlooms is largely inspired by Nesbit’s first children’s novel; the transformation of pure revenge (‘getting one’s own back’) into natural justice (getting the Adams family’s own heirlooms back) is in the same Nesbit tradition of using ideal or magical worlds “to work out real problems from their own lives” (as Colin Burrows puts it, Reflections 344-5).

There is so much literary treasure in this apparently artless story. I could mention the use of colour for example, exemplified by the rainbow which, contrasting with the drab surrounding neighbourhood, leads to missing treasure, or the diverse children — some West Indian or red-haired and others with disabilities or social deprivation — who somehow learn to work together in the face of a frightening external threat. To my mind there are few faults, and any that there are can be laid at the door of a debut author, such as the citation of specific monetary sums which, coming soon after the novelty of UK decimalisation in 1971, too soon fell prey to inflation and which appear laughably small four decades on. In addition, the quite literally colourful language that the gang of bullies use (what one might call purple prose turning the air blue) doesn’t always work: “get me my blanking Own Back on that blue-and-orange scum” starts to pall after a while. But rising above it all are Jones’ characters who, apart from the villainous of the piece, are not one-dimensional but variously recognisable from any social situation; Jones’ strength here is in allowing the reader to identify with any number of characters, not just the main protagonists.

I asked if it were possible for one short novel to have too many ideas, the range of which I have tried to hint at in this review. At the very least it must surely be preferable to a novel with too few ideas; but a book where you continue to make connections long after you have read it must be a very valuable one. Treasure seekers need not search in vain.

I agree, best to have too many ideas than not enough. At least it keeps you on your toes and engaged.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Certainly reviewing it kept me on my toes!

LikeLike

Can you please stop reviewing books. Every time I read one of your reviews I end up wanting to read the book, so I add it to my the bottom of my “books I don’t have enough time to read” list (not that I don’t read, I do, lots, it’s just that there are already too many on the list to read in my lifetime.)

The alternative is for you to work out a way I could grow another head. It’s your choice.

😉

LikeLike

Another head: you don’t need one, Dylan, because I read the books so you don’t have to! Mind you, I’m sure I’d be saying the same thing to you if and when you decide to review books on your blog too…

LikeLike

I don’t mind too many ideas as long as they do not get in the way of a well rounded story.

I have to be honest and admit that many of the ideas and references you mention would be lost on American children. Sadly we do not prepare our young for classical works. I have to wonder how many of these references even I would pick up on.

This is what keeps me back to your blog. I admire how easily you pick up on references and symbols.

LikeLike

To be fair, much of Wilkins Tooth is understandable without too much background knowledge: despite a proportion of it being culture specific, issues such as bullying, adult incomprehension and childhood obsessions and desperations are universal concerns, aren’t they. Though some online reviews seem to have difficulties with phrases such as ‘getting one’s own back — one comment was “I found the vernacular a little odd. I’ve read quite a few books by British authors, but still it seemed odd” — I’m sure that a significant number of readers look for books that at least challenge them a little rather than just give them the clichés they know.

And thank you again, Sari, for your kind words. A facility with references and symbols? Just a lifetime of eclectic reading and ferreting about!

LikeLike

It sounds like a roller-coaster ride, Chris. ‘m looking for a book to read Felix right now: this may be just the thing. Thank you.

LikeLike

I do hope this is up his street, Kate — lots of humour that ought to appeal to his age group. You might have to explain about the currency values, or multiply the sums by a suitable factor. I usually try and think what a Mars bar might have cost then (about four pence maybe?), then think what it might be now (sixty pence? more?). At least times fifteen then!

LikeLike

Pingback: March Magics: Two with witches – The Emerald City Book Review

Really enjoyed this review too and all the thoughts here — and look, Puss in Boots made it into the post after all, so you must have remembered it when you wrote this post! 😉 Delightful post. I too found that the story had so many ideas crammed into a short space and I loved that. It felt quite ready to expand out into her future stories. Good point about the Nesbit connection and Baba Yaga, too! I love seeing all these connections you’ve tied in to it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, Puss in Boots is definitely there, Deborah, even though I’d forgotten it! And I could also have referenced the transformations in the Welsh tale of Gwion and Ceridwen’s cauldron, or the metamorphosis sequence with Wart and Madam Mim in The Sword in the Stone. Nothing new under the sun, as they say!

LikeLiked by 1 person