Lizzie Ross Kenning Magic

Saguaro Books (2013)

You’ll look in vain for Mitlery and its neighbour Sarony in an atlas: they are to found only in the minds of their author and her readers. A miniscule map in Kenning Magic does at least help you orientate yourself: the western tip of Mitlery lies across a strait from Sarony (which we glimpse in the northwest corner of the map) while to the east are mountains harbouring goats and the creatures that prey on them. Rivers drain down from the mountains to feed into the Zilfur Zee, and habitations dot the land, from villages and towns in the countryside to fishing villages, ports and the country’s capital on the coast.

In a village in the centre of Mitlery lives young teenage orphan Noni. She’s different from everybody else in this land: in a country where magical ability is the birthright of every individual she is the exception. But what she does have is the ability to read, the ‘kenning’ magic of the title, and this grants her access to Oma’s book, an heirloom filled with tales and poems. When virtually everyone in Mitlery mysteriously loses their magical ability (apart from her friend Twig, a sixteen-year-old boy who luckily carries an apotropaic talisman) her reading skills give her and Twig the chance to find a way to restore magic to her countrymen as they set off on a journey to find the mysterious Book of Spells.

Lizzie Ross has, in Mitlery, created a believable secondary world, one inhabited by fallible humans similar to us and which has climates, seasons and physical geography that are easy to relate to and appreciate. These touches of realism are heightened by the accepted use of magic, the existence of creatures like dragons and the butterflies that feed off their scales (a singularly striking conception) along with the accepted fairytale convention that allows the meek to, if not exactly inherit the earth, at least prove the catalyst that rights the balance between good and evil. Because, of course, conflict resolution requires that there are two opposing sides and, as Ross notes in her acknowledgements, this story “began with the villains’ names and grew from there”. The baddies — DeBoyas and siblings Pintz and Wanda — are deliciously evil and clearly render the youngsters’ task of overturning their maleficence an uphill struggle.

I’m sure the target readership (around the 14-16 age of the two protagonists Noni and Twig) will find this a read that draws them in; as an adult reader I particularly liked the plotting which ensured that the fantasy was unputdownable. In addition to the thirty-six chapters (and an epilogue) there are the Tolkien-like nine appendices, nominally stories from the “Book of Tales by Oma, Rima’s daughter” that Noni inherits, and which have the Tolkienesque conceit of being “translated from Mitlerian” by the author. These for me were a real deepening of Ross’ secondary world creation: origin stories, fables, poems elucidating calendric lore, anecdotes, hints at sagas, all printed with a typeface that distinguishes them from the text of the novel. I can’t decide if I like these where they are at the end or whether they would work better interweaving the main story, perhaps after every fourth chapter.

There was much that I liked in this novel, but tighter editing would have made it even better: a dozen named individuals are thanked for their input, but a dispassionate editor would have upped the opening tempo and ironed out the few passages where I lost sight of character motivation (Pintz seemed particularly inscrutable to me), where the action at times seemed to be put on pause (the final denouement was a bit start-stop to fully convince me) and where Noni’s destiny seemed due more to happenstance than to the workings of Fate in the world of Mitlery. I also found the manner of indicating magic actions slightly clumsy (initial capital and inverted commas, as in ‘Reached’ or ‘Ascended’) — simple italicising might have been less distracting perhaps.

But this mild carping is only because I want Kenning Magic to be perfect: it embodies such wonderful concepts, such as that reading is a magical activity, a talent to be treasured as much as oral lore; that we can remain individuals and yet by working co-operatively achieve so much more; that evil-doers aren’t always completely evil in themselves and, while deserving punishment, should also have a chance to redeem themselves or be rehabilitated. Or, as the epilogue seems to suggest, that the villains have an opportunity to regroup, to pave the way for a sequel. And that is something I do very much look forward to.

A final word about the publication: Saguaro Books is a print-on-demand US publisher specialising in middle grade (ages 10-13) and young adult fiction written by first time authors. POD is a growing practice for new books with potentially limited first runs: in fact my copy, which I ordered from a small independent UK bookshop, was printed by Amazon UK, thus limiting shipping miles.

Ah, “apotropaic”. Like Vetch in The Wizard of Earthsea saying “Avert!” and “turning his left hand in the gesture that turns aside the ill chance spoken of.”

LikeLike

Exactly! ‘Apotropaic’ is currently one of my favourite words, along with ‘verisimilitude’ and ‘protagonist’ and a whole load of others! And ‘wonderful’, of course, as applied to Kenning Magic…

LikeLike

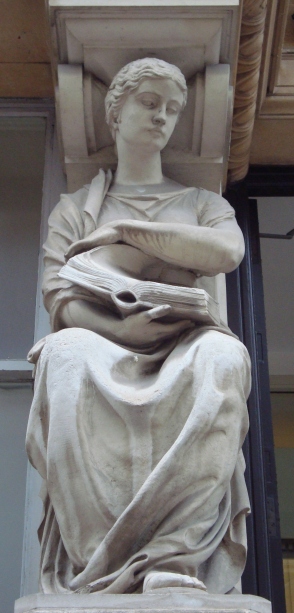

And I hope you liked the chosen illustration — it seemed appropriate to me.

LikeLike

Of course! Who can’t love a statue of someone reading? One of the ersatz (another great word to add to your list) gargoyles on my building is holding a book.

LikeLike

Don’t ever remember using ‘ersatz’, and only ever associated the word with coffee. Will have to find an apt moment to use it, but whether in its neutral or pejorative mode will involve some head-scratching!

LikeLike

In the case of the gargoyles on my apartment building, it only means they are decorative rather than functional: no spouts.

LikeLike

Congrats on such a spot-on review, Lizzie!

LikeLike

Ah, you must be the Libby Mark who ‘laughed in all the right places’! Glad you liked the review.

LikeLike

You are one careful reader. Did you note the cover artist?

LikeLike

I certainly did — another Rorschach!

LikeLike

We’re everywhere!

LikeLike

This seems to be the sort of book I would wish I had written. Great review!

You now have me worried in regard to my current magnum opus. I use words like Adapt for magical actions/things with a simple capital. I am now wondering whether italics would be the better option …

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sorry to worry you!

Verbs to me look odd with an initial capital, unlike nouns (does German still capitalise nouns?). To distinguish magical from unmagical actions italics (or even a different typeface if feasible) seem sufficient and not too obtrusive.

But please don’t take my word for it!

LikeLike

I like the idea of a different font, but I recall that in one of my earlier works the use of that for utterances of ‘Dreffles’ as well as using smaller fonts for people speaking in a small voice caused grief to publishers. Pratchett has effectively cornered the market with a nice simple upper case – IF I SPEAK LIKE THIS I AM DEATH.

LikeLike

YOU’LL HAVE TO SPEAK UP — I AM DEAF

LikeLike

🙂 Deathenitely.

LikeLike

I was completely enchanted with “Kenning Magic”… thanks for this review!

LikeLike

Pleased you liked it, Margaret! (And the review!)

LikeLike

As a fan of both Tolkien and Diana Wynne Jones, this sounds right up my alley! I’ll put it on my (always growing) reading list. Thanks for the suggestion.

LikeLike

Do hope you enjoy it as much as I did!

LikeLike

Pingback: The reliability of reality – calmgrove